Hollywood Psych

By Sean Collier

April 2, 2009

BoxOfficeProphets.com

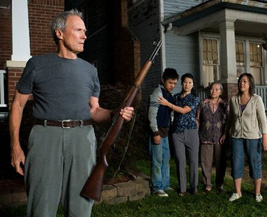

Clint Eastwood's Gran Torino is a very odd project and a very odd film. From the use of not only Hmong actors but also Hmong crew and workers to the odd reflection on Clint's career embodied in the character, the film is something of an uncanny experience, and a unique entry in a very diverse year of film. As the credits rolled, I remained in the theater, mainly to listen to the gorgeous, Eastwood-written title song; during the final moments of the credits, however, I noticed an odd disclaimer.

Immediately following the standard "No Animals were harmed" caveat was the following message: "No person or entity associated with this film received payment or anything of value, or entered into any agreement, in connection with the depiction of tobacco products."

To paraphrase, the note makes it clear that any smoking done in the film was purely an artistic choice, and not a form of product placement or promotion. Clint's character smokes like a chimney, and chews tobacco as well; the effect of these habits on his health is unabashedly presented, and he is chastised for smoking by his (admittedly antagonist) son. Additionally, without spoiling anything, the film's climax prominently involves Clint lighting a cigarette.

As recently as the 1980s, tobacco companies wrote large checks to get stars smoking on screen. Hollywood has since shied away from the practice, for obvious reasons (despite what you saw in Thank You For Smoking;) still, under pressure to make things as clear as possible, Warner Bros and Universal have begun putting disclaimers like this one on their films.

On the surface, this makes a lot of sense. With product placement as prevalent as it is in television and cinema today, it's somewhat natural to assume that the cigarette companies would try to get in on the act. They're desperate for positive press, and filmmakers love money. Additionally, while making a character smoke is something of a stock choice for a screenwriter trying to illustrate an aspect of that character's personality, it may not always read as such to the viewer.

I remember a conversation with my father on this subject after seeing Lost in Translation; did Philip Morris pay to have Scarlett Johansson puff away, or was this an artistic choice? My argument was that this was an attempt to highlight the directionless nature of the character. She had no vision of her future, no idea where her life was headed, and thus, behaved on impulse, which included continuing to smoke. At one point, she's asked why she doesn't quit, and she simply replies, "I'll quit later." My dad was unconvinced, however; it was such a minor aspect of the plot, and the character was clear without that indicator, he argued.

The disclaimer at the end of Gran Torino would head off this argument. Clint smoked for reasons related to his character; he was, after all, a defiant, angry old man with little regard for his own health and life. It makes perfect sense that he would keep up old habits.

There's nothing wrong with this acknowledgement. If we are to believe it, it allows us to forgive cinematic smoking to a degree, and quells concerns that producers are willing to compromise morally to cash in. What's dangerous about this, however, is the precedent it sets.

Say, hypothetically, that every studio follows suit. Just as any film with the briefest scene including an animal actor carries the "No animals were harmed" disclaimer, any film wherein an actor lights up will bear the "We didn't get paid to have that guy smoke" bit at the end. Wouldn't the logical conclusion involve a seemingly endless array of these caveats tailing the end credits? "The depiction of drug use in this film is not intended to promote these activities," followed by, "No gun or ammunition manufacturer donated or provided the weapons used in this picture," leading into "The use of racial slurs in this film is not intended as a hate crime," right before "The use of insults and vulgarity is not meant to promote schoolyard taunting and potty-mouths?" If we need a disclaimer explaining that a character choice is a character choice, aren't we really saying that we don't trust the audience to separate fiction from reality?

Furthermore, if we're going to begin using this particular brand of Hollywood ass-covering, doesn't this give ammunition to watchdog groups criticizing films without such disclaimers? Say, for example, a film has a similar character to Eastwood's in Gran Torino, who smokes and chews tobacco – in a way justifiable by the plot. Couldn't a group like Smoke Free Movies, alarmist decriers of big-screen puffing, accuse that film of taking big tobacco handouts because they neglected to include a disclaimer?

It's certainly a good thing that Eastwood and the other producers of Gran Torino didn't take a payout to have Clint smoke. It's not necessarily a bad thing that we're clear on that fact, either. But filmmakers feeling obligated to justify every character choice out of fear is not a positive thing for Hollywood, and it's a slippery slope from here to there. At some point, we're all just going to have to remember that movies are not reality, and are not telling us how to live our lives. Most of the time, anyway.