Chapter Two: Help

By Brett Beach

April 22, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

It is true that one of the first tapes I ever bought on my own prerogative - and not from a record club through the mail but an actual in-store purchase - was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. This was in 1987, the 20th anniversary of the album’s release and there had been an essay from a columnist I respected in The Oregonian to comment on the occasion, also noting that it was now the 40th anniversary of the day when “Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play.” Being 11 at the time, this last comment perplexed me to no end, a condition exacerbated upon listening to the title track for the first time and also wondering (although perhaps less profanely), “Who the hell is Billy Shears?”

I never really warmed up to the album. Was it perhaps internalizing guilt over references to drugs and sex and suicide and making time with meter maids that didn’t go over my head and made me at that age feel a little squeamish and ooky inside? I have a deep admiration for Sgt. Pepper as a piece, however (if that doesn’t sound too condescending), and “A Day in the Life” remains one of my favorite songs. It’s one of the best pastiches of musical ideas ever strung together, with lyrics that begin in mundanity and give way to empathy tied to a structure building to that final cacophony that stretches and stretches and . . . then seems to fade out for an infinity. Small wonder that Paul Thomas Anderson claims the song was a spiritual counterpart in his creation of Magnolia.

Still, I never went through a Beatles phase (Or a Goth phase. Or a metal phase, for that matter) My personal feeling is that this is a result of their status as a pop culture benchmark that any person born in the last 40 years is at least vaguely aware of. I wouldn’t go so far as to say I take them for granted, but perhaps that is an accurate assessment. And yet, I don’t think it’s the same for all bands with a similar level of world renown and all-pervasive familiarity. What is different about The Beatles?

To approach this answer from the backwards front (and through a slightly labored metaphor), I have always thought that it would be possible for me to love any musical artist, if only I heard the right song under the right circumstances at the right time. (Oddly enough, I do not feel this way about books or movies.) I visualize a key in a lock that I might have tried a dozen times before, and yet this time the lock tumbles. Is the lock different? Is the key different? Or is it the person placing the key in the lock?

Not to take away from The Onion’s humor, but Led Zeppelin was a band that I could appreciate in theory without every really “liking” or “getting” until I listened to two tracks from the live release How the West Was Won at a Borders listening station one Saturday afternoon in July 2003. The songs were “Over the Hills and Far Away” and “That’s the Way.” The snap-tight shuffle and stomp of the former (with its echoes of Tolkien) and Robert Plant’s plaintive little-boy-wounded vocals on the latter’s tale of love and friendship sundered struck the right nerves. Like the light bulb over a comic strip character, it was an “A-HA!” moment.

I suppose such a thing could happen with the Beatles, but it seems unlikely. And why? In one of the random thoughts that flies around my brain as I begin pre-writing in my head, it struck me that at the start of their career, The Beatles achieved an iconic status so instantly, that it must have seemed there would be nowhere to go but spiral downward or sky-rocket into oblivion. They charted 31 songs in the Billboard Hot 100 in 1964, a number as unfathomable then as it remains today. Six of those songs reached No. 1.

They won the 1964 Best New Artist Award at the Grammys (which should have been the kiss of death then and there, considering that everyone from Starland Vocal Band to Milli Vanilli has won it.) What now seems like one of the most spot-on and appropriate results ever in that category is I would argue actually a quite cynical bestowment, reflecting them as a commercial force too potent to be ignored, nothing more. Their debut film, also released that same year, both captured the zeitgeist of Beatlemania and had the daring to comment on it satirically. What would or could they do for an encore in 1965? More hits and another film.

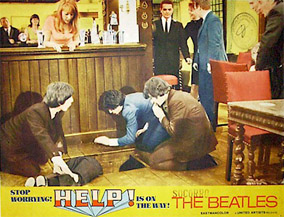

They “only” charted 11 songs that year, but five hit the top spot, including two of the 7 songs from their second film: “Ticket to Ride” and the eponymous tune. Help! reunited The Beatles (as they are referred to in the credits, not by their individual selves) with director Richard Lester for a 90-minute Technicolor lark - as bold and breathless as that exclamation point - that strives to incorporate and gently lambaste every film genre and cliché it can while at the service of a plot that somehow holds together while making absolutely no sense whatsoever.

There is a sacrificial cult, mad scientists, a befuddled Scotland Yard detective, battlefield shenanigans, Eastern mysticism, Western product placement, excursions to climes both wintry (the Alps) and balmy (The Bahamas) and interludes at Buckingham Palace, a recording studio, and the fourplex of adjoining apartments where John, Paul, George, and Ringo spend their down time (which in Help! lasts all of 45 seconds.) There are car chases, bike chases, ski chases, and an astonishingly high body count, including, I think, an entire contingent of The Queen’s Royal Guard.

And yet The Beatles fit snugly right in the midst of all this insanity precisely because of the iconic-ness I alluded to earlier. They had already become their own genre (generic in the truest and best possible sense of the word) and Help! reinforces and builds upon this sense of identification, that as a band they were already greater than the sum of their parts, if not quite bigger than Jesus. But they each retained a sliver of individuality that could allow someone to definitely choose one as a favorite over the others. This also applies to the logistics of the plot.

When the cult at the film’s opening is unable to proceed with their ritual because their intended victim is not wearing the sacrificial ring and the screen abruptly jump cuts to a projected black and white - the only such sequence in the film, a deliberate call back to their first film? - performance by The Beatles of the title song, who do we see has the ring on his finger? Ringo. Of course, it’s Ringo. The film doesn’t need to supply us with an explanation (although it does, off-handedly at some point and I’ve conveniently chosen to forget said circumstances.) It simply stands to reason that if a ring from a cult was missing, it would turn up on Ringo’s finger and he would be unable to get the ring off easily. That’s who Ringo was.

For their parts, all four of The Beatles were naturals at performing with an inherent charisma and a complete willingness to downplay and undersell their scenes and dialogue (as opposed to mugging and overt clowning) that is remarkably refreshing. The film feels as cinematically inspired and fresh as if it had just come out yesterday, and manages to avoid the trap of simply being a nostalgic document. Lester shoots the musical scenes in far-flung locations, in what might be described as prototypical music video but in each he takes care to capture the joy of performance. Whether it’s in a studio, on the slopes, or on a beach, The Beatles seem genuinely alive and electrified to be playing together. I think of a grin on McCartney’s face as a sun beam lights him from behind or Starr’s deadpan tambourine shaking as he sits in Lennon’s sunken apartment bed.

It would be an exercise in futility to attempt to chart the logistics of the screenplay as constructed by Marc Behm & Charles Wood but admiration must be given to any story that allows an on-screen moment for an escaped tiger who can only be soothed with a spirited humming of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. Interspersed with The Beatles numbers are more than a few classical riffs and references such as this that help place the band in a larger context while almost foreshadowing the day their songs would be deemed classic rock.

Having not seen A Hard Day’s Night yet (with its Oscar-nominated screenplay by Alun Owen) I can only hazard a guess that Help! comes off as more frenetic and vignette-driven than the former. A Hard Day’s Night would seem bound by its mockumentary approach and 36 hours in the life of time constraints while Help! suffers from no such restrictions. It strives for a sustained absurdity that heralds the impending arrival of Monty Python’s Flying Circus but is entirely too good-natured to crossover into that level of cut-throat take no prisoners satire and silliness. This everything-and-the-kitchen sink –approach certainly allows for any number of surprises as to where the action will turn to next but it also guarantees a certain raggedness and level of exhaustion, like a veddy British live-action take on a Looney Tunes theme. When the story simply forces itself to come to an end, to find a way to draw the curtain on the hijinks, it comes as somewhat of a relief.

Still for its energy, its music, its dazzling splash of colors (particularly as rendered in the print used for the 2007 DVD transfer) and for its furthering of The Beatles as icons in their own time, I am happy to have Help! Now just imagine The Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin having attempted something similar. Having a hard time doing so? Precisely.

Next time: Because really, why SHOULD everyone have to die at the end of Hamlet?