Chapter Two: Kill Bill Vol. 2

By Brett Beach

May 20, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

“Bill, it’s your baby.” --words uttered by The Bride just before she takes a bullet to the head.

Sometime in his lifetime (and I would hope my lifetime crosses over with this event) Quentin Tarantino will make a film where his protagonists just won’t quite get around to killing each other. I want to make clear upfront that this is not a lead-in to an indictment of the violence in his films. As brutal - and comically excessive - as many of these moments are and as feverishly as he stages the action surrounding these moments (particularly the fights in Kill Bill Vol. 2) with the aid and abetment of his longtime editor Sally Menke, the cost of the violence to his characters’ souls is always there in the sub/text.

Whether it is Jules Winnfield’s sudden decision to shed his hit-man mantle and “walk the earth”, Max Cherry’s weary resignation to grow old in his seedy profession, or Beatrix Kiddo’s resolute path of vengeance nearly undone by the revelation that her daughter is still alive, the cost of their violent ways or of the company they keep can’t be charged to life’s bar tab forever.

I have no doubt that in this rhetorical film, the threat of violence will hover in the air, explicitly and implicitly, as it does in all of his creations, but my thinking is that the characters will talk each other to death (ha ha) or they will enjoy the conversation too much to allow it to come to any sort of (final) resolution. Just as many of Raymond Carver’s stories resonate with the sense of an impending doom yet only a few actually build to a physically violent climax, Tarantino’s talking heads always seem on the verge of eventually lashing out at one another. Every tête-à-tête seems rife with the possibility that someone may end up losing his or her tête. And yet the words they wield as skillfully as weapons are so intricate and seductive and often pleasurable that it’s not inconceivable that they might not want to shut up.

These exchanges precede violence, postpone violence, and circle around violence. A love of language(s), storytelling and the gift of gab drives many of his characters and it amazes me how fresh Tarantino keeps the formula considering the number of times he employs it. A perfect example is this exchange between Stuntman Mike and Pam in Death Proof as he gives her a ride home:

“Well, Pam, which way you going, left or right?”

“Right.”

“Oh, that’s too bad...”

“Why?”

“Because it was a 50/50 shot on whether you’d be going left or right. You see, we’re both going left. You could have just as easily been going left, too. And if that was the case, it would have been awhile before you started getting scared. But since you’re going the other way, I’m afraid you’re going to have to start getting scared..immediately.”

It’s that always-underlying need to be scared that informs or should inform the lives of his characters. It is perhaps easier to think of the conversations in Vol. 2 that don’t resolve themselves violently - Budd and his boss; Beatrix and the aging pimp Esteban - than all of the ones, no matter how protracted, that do. (Beatrix and Bill’s final “Face to Face” fills up nearly a quarter of the film’s running time.) Yet even the two examples I just cited contain the possibility of a different, more brutal unraveling. The menace is palpable.

But what about the issue I have striven to avoid up until this point: Is Kill Bill Vol. 2 justified in its existence? Is it really just a limb hacked off of the first film’s cinematic torso? Much was made at the time of Miramax’ decision to avoid releasing one long film when filmgoers would most likely pony up for two trips to the cinema. Vol. 2 is notably longer in theory but this includes closing credits that run 14 minutes! (It must be said, however, Tarantino finds a way to keep them interesting up to and including the final Easter egg.) Money-grab though this may have been, the decision played out very well from a financial and critical standpoint.

Released in the fall of 2003, Vol. 1 opened with $22 million on its way to $70 million. Six months later, Vol. 2 premiered at $25 million while topping out at $66 million. Each, for a time, was Tarantino’s best opening weekend. Internationally, the two volumes performed similarly with the first out-grossing the second, a result that can be attributed to the more action/less talk nature of Vol. 1 and its extensive featuring of elements that had more pull abroad. The two parts tallied $110 million and $85 million respectively. With a budget estimated at around $60 million for the project and total worldwide grosses a smidge over $330 million, it’s easy to imagine that this pulled in at least twice as much as it might have if it had been a single long film or a severely chopped down (and lesser) one. Both installments received overwhelmingly positive critical praise and each sits with an 85% fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes.

Tarantino has promised (or threatened) for years now to put together an incorporated version of Kill Bill that restores the two volumes into a single whole four-hours-and-then-some magnum opus with re-jiggered opening and closing credits and some new footage edited in. While I don’t deny that this would be a fun epic cinematic experience (and this coming from someone who was uber-jazzed to see the near five-hour roadshow version of Soderbergh’s Che in part because all the credits were printed in a collectible booklet instead of being on-screen), I think that Vol. 2 not only stands on its own, but needs its separateness in order to maintain what makes it better than Vol. 1. The ten individual “chapters” that Tarantino divides the films into reflect a literary sensibility, but his titles and Beatrix’s to-kill list select a musical influence - a greatest hits collection, best of, or most appropriately, a Whitman’s Sampler of different genres. And in this sense, each film is its own creature.

In an ironic turn that is fitting given some of the plot twists in Vol. 2, it is the first part that feels to me like a series of (enjoyable) leftovers. Yes, Vol. 1 has the standoff with the Crazy 88 that is the cinematic piece de resistance of the films, but that sequence also feels like Tarantino giving the audience precisely, though deliriously, what’s expected, instead of finding a way to transcend himself and play with and tweak expectations, which he often does so perfectly he makes it seem easy.

The second installment digs deeper and resonates stronger emotionally. This is true even if one has not seen the first movie. Vol. 2 is Tarantino riffing on Sergio Leone and Douglas Sirk with equal fervor. Grandiose spaghetti-western showdowns and ridiculously amped-up domestic entanglements are conflated so that both become inextricably entangled. Instead of war waged in the wide open desert panorama outside Budd’s ramshackle trailer or a majestic sword fight on the beach outside Bill’s homey villa, there is a hilariously restricted battle within the cramped confines of Budd’s home and a brief, vivid (seated) exchange between Beatrix and Bill on his patio. Both scenarios are abruptly resolved by our heroine with a burst of violence wrought by her hands: an eyeball plucked, a heart exploded (internally at least).

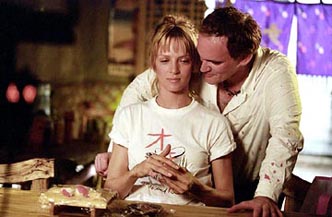

It would be condescending to say that Uma Thurman acquits herself nicely in the role. She delivers a performance high on both physical prowess and acute emotional resonance. There is an exceedingly short list of actresses who are believable both wielding weaponry and their heart on their sleeve in the same part. Linda Hamilton (Terminator 2), Geena Davis (The Long Kiss Goodnight) and Sigourney Weaver (Aliens and Alien 3) spring to mind and perhaps it is because all those films (and Kill Bill) involve women attempting to balance a fierce maternal instinct with a fierce killer instinct. Perhaps they are one and the same.

Tarantino sets up this theme of motherhood at the beginning of both films by using the same black and white footage of The Bride laying bloody and beaten and uttering the previously quoted line as Bill prepares to execute her. He employs it as the cliffhanger at the end of Vol. 1 as the audience learns that the daughter is still alive. However, it is a pair of quieter, heartbreaking moments that demonstrate Thurman’s perfect fit with the role that she and Tarantino co-created.

Upon awakening with a start from her coma in Vol. 1, she immediately clutches her stomach, reaching to feel the child no longer there. Tarantino allows her sorrow to play out several beats longer than one would expect and her pain is agonizing. This loss is inverted in Vol. 2 when she arrives at Bill’s home and learns the truth about her daughter. The emotions that play across her face, both controlled and barely contained, inspire well-earned tears from me.

There are a handful of performances that, long before becoming a father, I have always felt seemed transformed by the actor or actress’s perfect modulation in playing a grieving or otherwise distressed parent. To wit:

Ryan O’Neal and Marisa Berenson as parents beside their angelic young son’s deathbed in Barry Lyndon. Stanley Kubrick (!) plays this scene for every last shred of sentiment and heartbreak and loss and the surprise of that fact alone makes the scene stunning. O’Neal and Berneson are almost universally knocked as pretty faces and pretty vacant for their work here, a charge I have never understood.

Tom Cruise in Minority Report. Specifically for the scene in the hotel room where a cache of old photos sets him up to believe he has finally uncovered the identity of the man who kidnapped and killed his son years ago. The mingled tears of joy and sorrow and revenge as he declares, “I really am going to kill that man,” are both vindicating and terrifying.

Jennifer Connelly in Dark Water. As a mother going through a nasty divorce and on the verge of losing custody of her daughter, she has problems enough even before she begins receiving visions of a murder committed in the rundown apartment building she has moved in to. Looking older, more tired and more scared than at any point previous in her career, Connelly’s work here is even more impressive than her Oscar-winning role in A Beautiful Mind. Dark Water got lost in the wave of the J Horror remakes from last decade and is still seriously undervalued.

I would add Thurman to this list. If Vol. 1 makes Beatrix Kiddo a hyper-charged comic book heroine on a rampage, Vol. 2 makes her iconic. Whether punching her way out of being buried alive in a coffin or cuddling her daughter while sharing an entirely inappropriate bedtime movie, she is fierce and fallible. Towering and vincible. Larger than life and all too human. A woman, a mother.

Next time: BB Kiddo’s entirely inappropriate bedtime movie.