Chapter Two: True Stories

By Brett Beach

December 9, 2010

BoxOfficeProphets.com

A few reasons to take this column with a grain of salt: Talking Heads are my favorite band; I have a tattoo of the cover of their 1983 album Speaking in Tongues on my upper right arm; I interviewed David Byrne over the phone once, the subject was his performance on that week’s Sessions at W 54th St, a PBS music show he was also hosting at the time; others as noted below.

One of the common charges leveled against musician David Byrne’s 1986 musical serio-comedy True Stories is that it traffics in cheap shots and sustained condescension towards its subjects: the residents of a (fictional) Texas town as they prepare to celebrate the sesquicentennial, or 150th, anniversary of their beloved Lone Star State.

In many ways, this criticism bears remarkable parallels to the complaints hurled towards Joel & Ethan Coen over the last 25 years for numerous films in their oeuvre, but in particular towards early films such as Blood Simple and Raising Arizona, which boast similar geographic and socioeconomic landscapes. The Coens time and again have been met with accusations of sneering at their characters, mocking the predicaments and situations in which they place their creations, and standing back with an ironic distance that allows for superior smugness among more (supposedly) refined and urbane audiences. I don’t want to wander off into that rhetorical battlefield at this time, but I will note that O Brother, Where Art Thou played to a much different fan base than many other Coen films, particularly striking a chord with those in that nebulous cliché of a region known as “middle America.”

In the process, it became a medium-sized hit (the Coen brothers’ highest-grossing to that point) while never expanding beyond 867 screens at any one time. O Brother is easily one of my least favorite films by the brothers (along with The Ladykillers, it seems as if the Coens settled on shooting a far earlier draft of the script than they normally do) but I have to acknowledge that if I had seen it first in a different time and place than Manhattan in 2000, my reaction might have been considerably different.

I feel safe in this assumption because True Stories operates on a lot of the same principles (if not the same structure) and I adore it in all its meandering, quirky, and gentle lunacy. I first saw it when I was... well, for once my memory does not allow me to pinpoint the exact time and place. I can place the span roughly around the winter of 1987 when it was released on video, and it would be highly probable that my best friend JD was involved. As previously noted in “My Origin Story,” sleepovers at his house marked my first exposure to a wide array of individualized movie genres - ninja/martial arts, breakdancing, skateboarding, sword and sandal - and a surprising number of chapter twos.

I also have him to thank for whatever eclectic musical tastes I have been fortunate enough to indulge in, in the two decades plus that have followed. He turned me on to the Talking Heads, and, as they were the first real band I listened to with any regularity, consistency and depth, they were the template for all that followed. In my 20s as I listened to their albums with a fresh perspective, I began to appreciate how “weird” a lot of their songs were. I wondered if I would have so easily become enamored with their works if those listenings were my first.

JD could put on a good Byrne-tastic spaz show with the best of them. He lip-synched to “Making Flippy Floppy” at our elementary school’s first (and only) such talent show, put on by the fourth through sixth graders (as we were) for the lower classes and assorted chaperons during a week-long excursion to the Oregon Coast. He deservedly won. I floundered attempting a much too-literal take on “Yakety Yak,” acting out lyrics and such. I redeemed myself, after a fashion, not 12 months later tackling “Love for Sale” (from this week’s movie) and dervish whirling on my junior high stage like Iggy Pop, only without the broken glass and hard drugs. I didn’t win, but apparently the eighth graders - my elders - voted for me in droves.

(In the long run, however, I feel as if the essence of Byrne, his tics and mannerisms, have shaped me from the inside out, at least as much as I may have adopted them. If you want a glimpse of where I think I will be in two decades, bodily speaking, look no further than David Byrne circa 2010.)

In writing this week’s column, I have already offered up my personal biases that predispose me towards enjoying True Stories. I now confront a problem on the opposite end of the spectrum, a psychic Achilles Heel if you will, that I wrestle with on a regular basis and that may disallow me from seeing True Stories as it “really is”: telling when people are kidding.

I am terrible with jokes, relaying them and receiving them. If someone is pulling my leg, I can easily be suckered in. If they give up the game quick enough, no harm, no foul, I can be along for the laugh. If they were to sustain the joke, the story, what have you, indefinitely, with no winking, no breaking the illusion, just selling me the bill of goods and on and on, in the face of any evidence to the contrary, I would be forced to believe them. No matter how outrageous the construct. It’s like an existential riff on Sherlock Holmes’ theory that “once you take away the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the solution.”

As an example of this, I point to Joaquin Phoenix’s performance/art/stunt in I’m Still Here. From the start it seemed likely to me, as it did to many I am sure, that the Oscar-nominated actor was not really leaving behind acting for rapping and hiring his brother-in-law in the process to document behavior including but not limited to screwing hookers, snorting blow, and following a trajectory of spiraling assholery. And yet, as the months went on and no light escaped from that black hole, my thoughts did drift towards the notion that this was all for real. Perhaps he was mentally melting down and having it filmed, but it was not faked. With the truth at least somewhat come to light, I am glad to have resolution, though I would still qualify Phoenix’s behavior as sociopathic. Compelling and novel, worthy of Academy recognition, but distressing nonetheless.

Which brings me up to True Stories. A former girlfriend could not fathom my general disdain towards ironic affectation and distance and see how it could be reconciled with a love for and defense of this movie’s sincerity: “It’s nothing but irony, all the way through.” And there’s the rub. If the movie is a solid wall of post-modern hipster stick-poking at small-town yokels, it is so complete and thorough that I have no choice but to consider it sincere. Thankfully, I do have some externals and other mitigating factors to rely on in defending this decision - Byrne’s words regarding the project, a glance at his collaborators, the look and tone of the picture, the role Byrne’s narrator plays in the film - but I also have my childhood spent in at least one version/variation of small-town Americana.

In the illustrated official screenplay - containing many scenes and subplots that were cut to obtain the 89 minute running time - that accompanied the film’s release, Byrne notes that the genesis for many of the film’s characters and ideas was the tabloids that people always linger over in the checkout lanes as their vegetables and canned goods go down the conveyor belt. He admitted that there was a part of him that always wants to believe those stories are, well, true. Is he being sincere? This is, after all, the same individual who staged dramatic readings of transcribed game shows for fun while he was in college, and whose most recent musical effort was collaboration with Fatboy Slim on a pop opera suggested by Imelda Marcos’ life. Quirk and kitsch have been the fodder for many of his inspirations.

I feel as if he has always approached the topics of his art with the intentional naïveté of a child, the need to see things from a different perspective, less jaded or cynical. It probably isn’t a coincidence that True Stories opens with a held shot of a young girl walking down a dusty road towards the camera making bird calls and other noises and closes with her retracing her steps. His film seems as innocent at times as that youngster and though it walks a fairly straight narrative line from beginning to end, it is adorned with oddball behavior.

Byrne directed and co-authored the screenplay for True Stories, receiving an “and” credit in the final accordance, alongside the ampersanded team of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Beth Henley & long-time milquetoast character actor Stephen Tobolowsky. For nearly 25 years I have looked at those names and wondered, as no doubt you do, “How the hell did that collaboration come about?!” I finally determined to answer my own question. Henley and Tobolowsky were an item for a number of years encompassing the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, stemming from the fact that the pair attended Southern Methodist University at the same time. Both were born, as Byrne was, in the early ‘50s and the two of them hailed from the South and Midwest: she from Mississippi and he from Texas.

I have no way of categorically determining who brought what to the screenplay, but I do feel that the film is stronger for having multiple voices bringing life to Virgil’s citizens. If Byrne’s sole intention was to satirize and mock, he could have easily written those barbs himself. By working with creative types that he evidently felt a kinship with, and who had grown up in the milieu in which the film would be set, I feel his true intentions towards the project are brought into focus. But whence this gravitation towards the Midwest?

I have always considered True Stories a follow-up of sorts to Talking Heads’ tune "The Big Country,” the twangy shuffle that ends their divine 1978 album, More Songs About Buildings and Food. The unnamed narrator of “Big Country” spends his life in planes observing urban and then small-town life reaching the early conclusion that he “wouldn’t live there if you paid me to” before deciding in the end that he “needs to be somewhere” and he will take his chances on land.

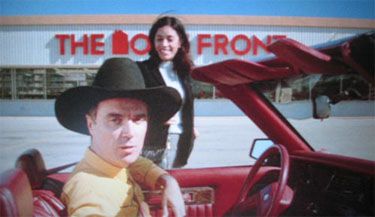

Byrne plays the unnamed narrator in True Stories and he may be the same individual from the song. He is our guide to the town, an outsider who still seems to be “in” and who knows and/or is accepted by most of those he meets. His most notable aspect, aside from the ridiculous outfits he sports in a nod to local fashion, is a stop-start deadpan vocal pattern that makes mincemeat of punctuation and renders his thoughts more rivers, than streams, of consciousness. For example:

“I had something to say (pause) about the difference between American (pause) and European cities (long pause) but I forgot what it was (pause) I have written it down somewhere at home (very long pause) Look (pause) I personally believe (medium pause) I can see Ft. Worth from here.”

It wouldn’t be appropriate to address Byrne’s acting style as such, except to note how he allows the narrator, with his complete lack of affect (and a pulse) to serve as an ideal blank slate for those around him to bounce conspiracies, rumors, and ideas off of. He is only a city slicker at surface level. To all appearances, he is as refreshingly cracked as the townspeople themselves. But who is he and why is he there? I have one theory that I will put forth at the end. But first, I want to briefly focus on the music, the cinematography, and a few of the other performances.

There are nine featured songs in the film: six are performed by cast members, one is a lip-synch at a club to a “Talking Heads” song, another is a music video/commercial featuring the members of Talking Heads performing/becoming a commercial themselves and the last is performed by the band over the closing credits. Initially, there were going to be two soundtrack albums: Sounds from True Stories, with instrumental pieces (there are over a dozen) and a few other minor songs with vocals; and an album featuring the songs as performed by the cast members. The former did come out but only on cassette and LP - it has never been released on CD - and the latter was scrapped in favor of an album featuring all nine songs being performed by Talking Heads. Thus, it is not technically a soundtrack but it is the weakest of their eight studio releases.

There is an unfettered joy in the performances by the mostly non-professional singers: John Goodman’s country-tinged growl on “People Like Us”; Annie McEnroe’s lighter than air quiver on “Dream Operator” and John Ingle’s spoken/sung throaty rasp delivery of “Puzzlin’ Evidence.” The menagerie of faces lip-synching along to “Wild Wild Life” suggests an early form of karaoke and the communal nature of passing the microphone off after a line or two reinforces the sense of community (odd though it may be) that Byrne has infused the film with. It is indeed the same joy of performance that Jonathan Demme bore witness to in filming Stop Making Sense.

For the longest time, I have bemoaned the beyond bare-bones DVD release of True Stories. No menus, no extras, full screen. For a cult film with a highly visible presence 25 years after its release to be treated so shabbily remains insulting to me. But with the chance to have seen it in the theater in 2002 in Brooklyn, with Roger Ebert interviewing Byrne, taking questions and then screening the film, it must be said that Ed Lachman’s cinematography does not suffer from being seen on the small screen.

This is because the film was, to my understanding and supported by the print show, shot in 1.37:1 aspect ratio, that is, barely more than the television ratio of 1.33:1. Thus, what would be a pan and scan in most other instances doesn’t suffer from being shown at “full screen.” The outdoor vistas capture the sprawl of Virgil and the push of the still-expanding town against open fields, even without widescreen. But Lachman coordinates his interiors carefully as well, particularly in the sequence set in Virgil’s main shopping mall, where the hustle and bustle going on around the narrator as he strolls the promenade doesn’t feel boxed in The primary colors also pop off the screen with an intensity that fairly reminds me of mid-1960s Godard such as Two Or Three Things I Know About Her.

With its collapse of high fashion, music videos, commercials, mall culture and small-town civic pride into a giant musical Pop Art stew, True Stories was slightly ahead of the curve in its time and still feels fresh in 2010, not entirely an ‘80s-fueled nostalgia trip. This was Goodman’s first major lead role and he has rarely been so emotionally vulnerable, self-deprecating and disarming. He is the face of Virgil and his gentle and honest demeanor sets the tone for much of what follows. Spalding Gray appears in only three scenes but one involves an economic allegory played out at the dinner table (bringing new meaning to playing with your food) that ends with his frantic enjoinder to his children, “Linda! Larry! There’s no concept of weekends anymore!” His over-ingratiating manner endeared him to my pre-teen self and Gray remained one of my favorite performers/personalities until his suicide in 2004.

To close out, I wanted to return to my theory about the nature of the narrator. Part of it is inspired by one of the scenes in the published screenplay that’s not in the movie - a funeral for one of the main characters that brings together a large chunk of the town; and part of it is from a quote in a review of the film that likened it to Our Town, Thornton Wilder’s quietly aching portrait of the beauty and sadness in day-to-day life. I think the comparison is apt, even more so if the narrator is looked at like a benign angel of death, biding his time in town, the ultimate outsider, but still on quite intimate terms with everyone. The people of Virgil are happy to be alive, even as they know, as indeed we all do, that there might be nothing coming after tomorrow.

Next time: The year ends with... 1930s German Expressionism? An estrogen-fueled romp through the Middle East? Something else entirely? I have yet to decide...