Chapter Two - Mission: Impossible II

By Brett Beach

March 3, 2011

BoxOfficeProphets.com

This means that quite possibly it will never be released in theaters over here and will be quietly shuffled off to home video; and/or it will be heavily re-edited at the behest of Harvey Weinstein in order to alleviate any potential plot confusions that might cause American moviegoers discomfort and distress; and/or Woo (as co-producer and co-director) will be encouraged to chop out any multiple utterances of “Shit!” “Fuck!” or “Tits!” in order to secure a family-friendly PG-13 rating. This is neither the time nor the place for me to go into my long-brewing Glenn Beck-esque “crazy man” rant against what The Weinsteins hath wrought in their 20-plus years in the production and distribution business. I will simply address the Academy and the Governors Board and say: The Weinsteins were on the ropes. You brought them back from the brink with The Reader’s five nominations two years ago and now they have their Oscar mojo fully restored. Heaven help the next wave of foreign filmmakers looking for an “in” to the American market - if such a thing is even possible anymore.

This column marks both a first and (not as exciting for several reasons) a second. Woo is the first filmmaker I have featured twice (I wrote about A Better Tomorrow II back in August 2009) and this is the first time since one of my earliest columns — Scream 2 back in May 2009 — that I have been deeply surprised how much a fairly positive opinion of a film, flickering steadily over the years, has been snuffed out by a second viewing. I have seen the first and third Mission Impossible-s several times since their respective big-screen debuts in 1996 and 2006 and find that both hold up well, in my estimation (more on them in a little bit).

I had not seen M:I-2 since its Memorial Day weekend bow back in 2000 — a mere three weeks after I had gotten married and two months before I was set to move to NYC for graduate school. It's unclear whether I was still basking in the afterglow of the nuptials, the before-glow of continuing my education in lower Manhattan, or I was simply desperate to shed any lingering impressions of Battlefield Earth from my conscious thoughts.

Watching M:I-2 last week, in between rounds of keeping my son entertained as a rare late February snow day in Portland closed the public school system and his daycare as well, proved to be a disheartening experience. The first half is a cavalcade of references to Hitchcock masterpieces and the first Mission: Impossible, and the second half is either Woo on autopilot or Woo pushing himself past the point of parody (something I would not have thought possible) and back to an almost rote directorial style marked by recognizable Woo flourishes, but missing the giddy sense of “Can I top this? Just watch” filmmaking that make the best of his films both operatic and intensely moving.

In order to further advance my expression of my disappointment, I think it’s important to look at M:I-2 in the context of the series as a whole, where each film has a different director, and that director’s authorial vision is allowed to stand out to a large degree, and as the film fits in with Woo’s decade-long “American experiment” (as I am calling it) where he came to Hollywood and between 1993-2003, directed six feature films, two made-for-TV movies and a failed pilot (apparently for a Lost in Space reboot).

With a $91 million opening over an extended Wednesday-to-Monday holiday period and a final gross of $215 million domestic, Woo’s take on the further adventures of Ethan Hunt is the most successful in the series and his career, from a purely financial standpoint. After delivering the well-received and unexpectedly blockbusting Face/Off for Paramount back in 1997 (when Nicolas Cage, Action Star was a new suit that audiences were still enjoying breaking in), Woo chose to go the director-for-hire route once again instead of a more personal project.

Beginning with Hard Target, and continuing with Broken Arrow and then Face/Off, each of his films had grossed more than its predecessor and allowed Woo increasing leeway for both his highly stylized violence/action sequences and his feel for the grandly melodramatic passions of his characters to take center stage. M:I-2 continued the building success on the money end of things, but with a $125 million budget at his disposal and the fate of a franchise on the line, Woo’s signature vision, which he was no doubt hired/recommended for by Cruise, suffered.

Somehow Brian DePalma and J.J. Abrams sidestepped this fate. DePalma’s take, my personal favorite, is very much his own beast — until that shoehorned-in bullet train/helicopter climax — and the air of 1970s paranoia and governmental mistrust that pervades the story and Hunt’s pursuit of the truth, feels like DePalma in Blow Out mode. The defining image, Hunt breaking in to the CIA from above to enter a secure computer room and upload a file in utter silence while dangling from a wire, is perversely thrilling and completely antithetical to the normal visceral charge of a big summer action set piece. To a lesser extent, this is true of the conversation between Hunt and one of his superiors (played with steely resolve by Henry Czerny) at a restaurant that climaxes with a literal bang and the endlessly quotable line from Hunt, “You’ve never seen me very upset.”

J.J. Abrams’ take on Mission: Impossible has been the best received from a critical standpoint and finds favor among many of the staffers here at BOP. Philip Seymour Hoffman certainly embodies a more boo-worthy and ruthless villain than Dougray Scott or Jon Voight is able to. Abrams finds his preferred balance charting the conflicts between the equally worthy yet stress-inducing travails of his protagonists in their personal and professional spheres, and stirs the pot with a requisite amount of double-crosses and game-changing plot twists. If it on occasion feels like a missing arc in one of the final seasons of Alias, Abrams pulls off the neat trick of keeping the ridiculous spy elements at a light summer action simmer while his characters' emotions are allowed to bubble over.

Where do M:I-2’s problems begin? Laying complaints at the feet of the film’s soundtrack may sound odd, but a Metallica closing credits number and Limp Bizkit’s nu-metal interpretation/interpolation of the theme music not only feel wrong to close out the film, they suggest a completely different feature that has taken place over the prior two hours. Academy Award-winning screenwriter Robert Towne was co-credited on the screenplay for the first Mission: Impossible and received sole credit for M:I-2. Instead of Chinatown originality, there are homages and rip-offs and a concerted effort to recall Towne’s own screenplay for Tequila Sunrise.

The first half of the story involves plot points and references mashed up from any number of Hitchcock films. To Catch a Thief is directly called out. The strategy of a spy sending in a non-professional to get romantically involved with a target (after said spy has fallen for his charge) is straight out of Notorious. The stylish compound where Sean Ambrose (Scott) lounges around with his henchmen is a nod to James Mason’s abode near the face of Mt. Rushmore in North by Northwest and Ambrose’s relationship with his right-hand enforcer Hugh Stamp, which is built on all sorts of suppressed romantic feelings on both sides (Ambrose can slice off a tip of Stamp’s finger with a cigar cutter, but he can’t kiss him!) is a parallel to the relationship of Mason’s and Martin Landau’s characters in that film as well. All of these ideas are noticeably, if uninterestingly, set up in the first half and not one of them pays off in any meaningful way in the second half, which is dominated almost entirely by action.

A break-in to a scientific lab where Hunt must destroy samples of a biological weapon (M:I-2’s version of a MacGuffin) attempts to blatantly up the ante on the similar scene in the first film, but devolves into the expected glass-shattering shoot-out, with Cruise and his gun seemingly unable to miss against Ambrose and a dozen of his goons. Cruise’s unexpected exit out of the building at the end of the scene provides a quick jolt of adrenaline but then the storyline futzes its way through to get us to an extended finale featuring what can only be described as motorcycle-fu and a final mano-a-mano between Hunt and Ambrose.

The bloodlessness of this encounter and most of the others in the film combined with the rapid-fire editing to suggest excessive violence feel like pale approximations of Woo’s late '80s and early '90s Hong Kong glory days. Cruise is filmed multiple times in dreamy slo-mo whipping the tail of his jacket up behind him, the better to slide out a hidden gun from his waistband and take aim at...life and if he never quite achieves Chow Yun Fat zen, it’s a fairly amiable approximation for these shores.

What Towne and Woo aren’t able to approximate is a through-line for Nyah Nordoff-Hall, Thandie Newton’s ill-conceived character. She and Hunt strike palpable sparks during their first meeting and Towne creates a genuine feeling of conflict for Hunt in sending her back into the arms of her prior boyfriend Ambrose to help determine his role in the theft of a supervirus. But after giving Nyah an incredible scene of sacrifice halfway through, Towne all but disappears her until the closing minutes. I am not saying Nyah needed to be joining Ethan in double-fisted gun orgasmica, but it’s a waste of an actress and a character. On the flip side of that, they do find a way to keep character actor and Armin-Mueller Stahl doppelganger Rade Sherbedzija popping up, even after his character dies in the first three minutes.

To circle back to that opening scene and the two that immediately follow it, Woo and Towne create an air of unease and mild distaste that hang a pall over everything that follows. They’re not the sort I associate with either gentleman and they do color my response to the rest of the film. The opening “sting” on the airplane that ends with the bad guys escaping and everyone on the plane unconscious would be shocking in and of itself, but before the plane is obliterated, the co-pilot groggily recovers long enough to see the plane about to crash into a mountain and the audience is invited to share his terror at his and everyone else’s impending death.

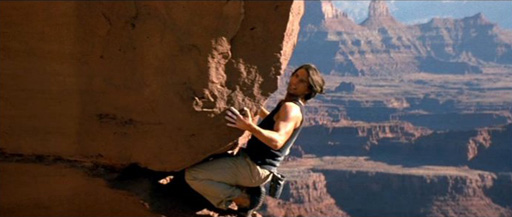

Cut to Ethan rock climbing with only his hands at Dead Horse Point in Utah. At one point he pivots around so his back is against the rock side and he stares directly at the audience for an unnaturally long time. The sequence as a whole exists almost entirely outside of the rest of the plot (unless taken as an example of Ethan still working off the events of the first film) and that pointed gaze, part desperation, part wildness is extremely unnerving.

Anthony Hopkins pops up in an unbilled cameo as Hunt’s boss in the third scene, playing his part with an almost reptilian, disinterested air. He gets the funniest line rebuttal in the movie - “This isn’t Mission: Difficult, Mr. Hunt, it’s Mission: Impossible. Difficult should be a walk in the park for you” — and finds something ominous and chilling lurking between the lines, the camera settling in on his face in close-up.

Now, when I think of M:I-2, it’s not the signature Woo birds (pigeons this time) as harbingers of battles to come that I remember, it’s those three faces, terrified, desperate, and disinterested, that come to mind. Whatever they suggest, they do not point the way towards the disjointed action flick that follows.

Next time: “You’re gonna get what you deserve.” At 45, he is now an Academy Award winner and a new dad/first-time changer of diapers. Under his own name and the Nine Inch Nails moniker, Trent Reznor has unleashed some of the most danceable head-banging industrial rock of the last two decades. His albums proper have topped the charts and sold millions. But what about the Nine Inch Nails remix albums? I feel that’s where his true musical genius rests. In a one-off wholly music themed-column I’ll look at Fixed, Further Down The Spiral, Things Falling Apart, Still, and Y34RZ3R0R3M1X3D, and consider what these musical Chapter Twos have to offer in relation to the albums from which they were borne.