Sole Criterion: A Hollis Frampton Odyssey

By Brett Ballard-Beach

July 5, 2012

BoxOfficeProphets.com

I am not sure if it can be counted as a digression if I choose to start with it, but I felt an extended anecdote was in order for my introductory comments. Late last fall, I had the chance to see a film titled 13 Lakes, which as its title suggests, concerns a baker’s dozen of the titular bodies of water, all from the United States. Each lake is featured for precisely ten minutes. The camera is fixed, several feet off the water, and does not pan or zoom. The image is perfectly centered, capturing an equal amount of water and sky. (In the case of Crater Lake, southern Oregon’s world famous landmark, the reflection of the mountain peaks in the water is so dizzyingly symmetrical it becomes easy to understand how a small plane once crashed in the lake when the pilot became disoriented and lost his bearings.).

And on the soundtrack, a wealth of aural pleasure that becomes an almost narrative for each piece: a speedboat that comes into frame every so often as it loops around one lake; gunshots like muffled firecrackers off in the distance during another; a train that comes speeding along, ever so frustratingly just out of sight, and then recedes, the roar of its engine fading over much of the remainder of the running time. Each segment allows for contemplation and (yes!) boredom, reflection and distraction. Many of James Benning’s films deal with the physicality of landscapes and geography, measured out in formal units of time.

I had been hotly anticipating this film, based solely on the description provided by the group screening it and an affinity for prior work by Benning. I had booked a Zipcar with enough lead-time to get me to the Hollywood Theatre before 7. This was the second of a two-night programme and the previous night’s screenings had started ten minutes late. I felt confident. I had not counted on my first experience with a car being returned late. Nearly 20 minutes late. As the half o’clock turned to quarter to seven, I began to calculate: “I can make it there and miss a minute of the first lake. Three minutes. Half.” I began to go back and forth in my head—“Do I go if I know I will miss all of the first lake?”

I tore out of Reed College parking lot at 648 pm up towards Cesar E. Chavez Boulevard. From there, it was a left turn and a straight shot of nearly 70 blocks. Providentially, I hit nothing but green lights all the way north, during the tail-end of rush hour, and but for searching for a place to park at my destination would have made it on time. As it was, I parked two blocks away and dashed across a busy intersection, tore through the front door, sprinted up the flight of stairs and threw my admission money at the hapless volunteer.

I wound up being about six minutes late, which still wounds me. But, as you might imagine, sitting and staring at a scene of natural beauty does wonders for one’s composure when one is red-faced, breathless and about ready to pass out. I was as excited to see 13 Lakes as I have been studio tentpoles in summers past, and it remains one of the most enjoyable and involving films I have seen in the last year. I relay this story to give you a baseline by which you can suss out my personal affection for non-narrative films, specifically ones built around a tight structure, an identified time limit, and a willingness to create a private universe in miniature. The director who is the focus of this week’s column created short films that might be reasonably viewed as controlled scientific experiments or conversely, mathematical equations and proofs set to 24 frames per second and overflowing with an artist’s humanity and vision.

The film leader that opens several of Hollis Frampton’s pieces contains the word FOCUS (in similar typography to the 10, 9, 8… countdown many of us of a certain age are familiar with from the educational films screened in junior high and high schools.) In its primary and most obvious form, this is an instructional device to the projectionist to help him or her clarify the image, as the film is about to start. But coming from a filmmaker who so carefully selected and assembled the elements of his films as much from mathematical precision and scientific inquiry as from the aesthetics of art, poetry, and still photography that had been his earliest foci, it becomes well as much a command for the viewing audience.

The recent Criterion release of A Hollis Frampton Odyssey marks the first collection of Frampton’s 16mm (some b&w, some color, some mono, some silent) films on DVD. The 24 pieces in question (28 if one counts the four one-minute “pans” that are used as menu background animation on the two-disc set) span 1966-1980, range from barely one minute up to just under one hour, total nearly four-and-a-half hours and are helpfully categorized into four subsets: early works, three representations from his seven-film opus Hapax Legomena, 15 pieces from his Magellan project (a massive artistic undertaking that was interrupted by Frampton’s death from cancer at the age of 48 in 1984) and Zorn’s Lemma, the almost feature-length work that became the first example of the American avant-garde to be selected for the New York Film Festival. I can’t even hope to give more than cursory information or insights in my limited space, but the accompanying essays in the collection provide explicitly detailed analysis and historical framing.

Frampton cuts an amusing though slightly difficult pose in the interview excerpts and brief framing comments that are available as extras (the audio-only comments may indeed be taken from the featured interview, conducted in 1978). He has wildly unkempt hair, chain smokes like cigarettes were going out of style, and speaks in a monotone nasal, pausing at such irregular beats, he may well have been David Byrne’s inspiration for his narrator role in True Stories. At times, he seems like Jim Henson’s beatnik brother, and other times, when he makes direct eye contact and seems intent on staring down the camera, he becomes more than a little unnerving.

And yet, all of this is contradicted by his words, which he seems to choose for maximum comic effect. I don’t know if martini dry can aptly encompass his wit, perhaps bone dry? I can’t begin to replicate his audio on the written page, but there is more of a self-deprecating bent than one would expect, and an insistence on pausing to find the precise way he wishes to express himself. I don’t doubt that he did not suffer fools gladly but he seems able to balance a strong ego with a knowing wink in his own direction.

I have had the opportunity to see the three longest pieces included in the Criterion package on film at various points over the last decade: Zorn’s Lemma, Winter Solstice, and (nostalgia). The first and last were screened as part of classes I took at NYU, and the middle one was shown by a local Portland collective known as Cinema Project that holds twice yearly programs of avant-garde cinema each featuring about a dozen screenings. (nostalgia) made such an impression on me at the time, and continues to, that I would be accurate in assessing it as my favorite short film of all time. It, alongside “The Body” episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer - see my November 11, 2009 Chapter Two column “Buffy, Baby, and Brett for more on that - has given me more to ponder about the nature and meaning of memory and loss than any other piece(s) of filmmaking that I have encountered.

The elements of (nostalgia) are bracing in their simplicity: A narrator recounts the histories behind 12 photographs taken by Frampton, most from at least ten years prior. As the narrator speaks, each photograph is seen resting on what the audience soon discovers is a hot plate. As each (approximately) three-minute anecdote is related, the photograph smokes, smolders, and soon is consumed by the heat. If the photo burns quicker or the story is shorter, than there is silence on the soundtrack, as the husk of the photo crumbles and ash takes to the air.

The first catch is that in each case, the narrator is not describing the photo we are then looking at, but the one that is next to appear. Thus, the film begins with a photo that has no story and ends with a rather breathless, purposely cliffhanger-ish encapsulation of a photo that we will not see. In the other instances, we must keep the narration from before fresh in our mind to see how the photograph compares to the image we have created. This comparison must then be done in the “shadow” of paying attention to the current description. It’s like a slightly more cerebral cinematic take on the childhood game Concentration.

The second catch is that, though the narration is all first person about Frampton’s life and experiences, he isn’t the one talking (save for a few utterances during the first few seconds). Fellow avant-garde filmmaker and friend Michael Snow handles the speaking duties and his Canadian accent and more overt embrace of the humor in Frampton’s text shift the vibe from Frampton’s erudite professor to more of a Garrison Keillor of the Great White North. Frampton’s words are often critical in their self-analysis and the 36-minute film could be seen, on a most basic level, as an act of anti-creation, of placing one’s artistic endeavors on the funeral pyre. (It should be noted again, though, that these are still photographs burning, not negatives, leaving open the possibility that they could be “recreated”.)

In the simple disjunction between word and image (which he takes to its most extreme limits when he charts a relationship breakup in his work Critical Mass), Frampton suggests the way in which the “fact” of the past can become entangled by and wrestle with our memory of the event, or become rewritten through changes in ourselves over time, or by the act of forgetting what once seemed so important to document for posterity. Frampton was 35 when he filmed (nostalgia) and looking back on photos he had taken from his early to mid-20s. Whether it’s from Snow’s intonation or Frampton’s embrace of the parenthetically qualified emotion of the title, the film resists the condescending examination of someone older looking back on his youth with superiority or some “there but for the grace of God go we all” ennui. There is an element of melancholy and more than a dash of wry humor, but the stories and the project itself are marked by the skill of taking an honest account of a handful of moments in a life, and stepping outside of that history in order to do so.

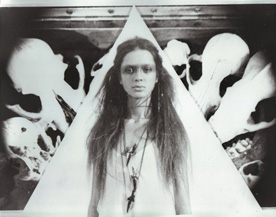

All of this is enhanced by the centering of each photograph on the hot plate and in the frame, permitting the cloud of smoke to arise as if out of nowhere before the spiral of the hot plate element becomes seared into the picture, and often allowing someone’s face to be perfectly aligned so that it remains as the final portion of the photograph to become blackened (note this particularly in regards to Frampton’s self-portrait.)

Throughout the films that make up this Odyssey, Frampton shows a remarkable feel for capturing the physicality of someone’s features in a matter of seconds. This is noticeable from the outset in 1966’s Manual of Arms, a b&w silent film featuring appearances by the close-knit group of Manhattan artists with whom he was friends at the time, each represented in quick succession and later in a more “extended” offhand manner (the film runs 17 minutes). The pair of drama students who became his first actual actors - in 1971’s Critical Mass - play at a Cassavetes-like improvised domestic squabble, and Frampton structures their flamboyant gestures, profane epithets, and defiant tones by allowing the audio to lose sync with the image, or repeat the recorded sound in triplicate, like a scratched record echoing in a cave. The man and woman are no longer on the same wavelength, and neither are their words.

Magellan was meant to be a 36-hour collection of 1000 films, to be viewed over the course of a full year and then some (ever a master of structure and form, Frampton created his own calendar for this project, and had most days plotted with their programming, even if the films were more conceptualized than realized at that point). A six-minute excerpt from one of these pieces features a wholly unsettling employment of canned audience applause on the soundtrack. Thinking about it even now makes me queasy. I can only describe the sound as the falsely jovial hand claps of the eternally damned, as if Frampton had drained the warmth out of a simple human gesture. Furthermore, the manner in which Frampton deploys this on the soundtrack, delaying it or even withholding it, but always returning to it produces a dread anticipation of Pavlovian proportions.

The collection counters this with one of the last sequences Frampton filmed for Magellan (and one that would have chronologically been shown at the very end of the cycle). Gloria! is a warm and humorous tribute to Frampton’s grandmother that culls together inspiration from Finnegan’s Wake, presents its raison d’être via scrolling text on a computer screen and climaxes with a bagpipe extravaganza that gets a big laugh by tying back in to an earlier moment in the film. Venturing out into computer technology in the latter years of his life, Frampton found a way to imbue wires and circuits with a remarkable facsimile of humanity.

There are an abundance of these small moments that I could focus on, but there is one in particular with which it feels appropriate to close. Zorns Lemma takes its name from a mathematical proof, and indeed it seems as if it could be translated from film into an equation. It runs 59 minutes and 51 seconds (in this case “approximately” an hour will not suffice and God bless Frampton for not trying to squeeze another nine seconds in there.) There are three parts, running three, 46, and ten minutes respectively. The first part features voiceover but no image (simply black leader). The second part features an ever-revolving panoply of 24 images, cycled through 115 times, with no audio. The third part features a winterscape image (complete with man, woman, and dog walking off into the snowy woods) held for ten minutes, with a liturgical recital on the soundtrack. In his audio comments, Frampton notes that the first and third parts are there to bring you into and take you out of the middle portion- to clear your mind and cleanse your palate, as it were.

And about that second part. In a (not so condensed) nutshell: 24 images in a cycle referencing both the 24 letters in the Latin alphabet and 24 frames per second of film. The letters are represented by NYC street signs that begin with “a”, “b,” “c”, etc. Slowly, but surely, the letters/words are replaced with straight images. Some of these images are static (“y” becomes a raging hellish bonfire and remains so henceforth) while others become little picture stories (where “t” once existed, a man changes a tire, for “p”, the tying of shoelaces.) The game of finding the word for the letter, becomes the game of which letter will get switched out next, becomes the puzzlement of what new image will pop out. Even parsed out at only a second at a time, this part of Zorns Lemma reinforces Frampton’s skill, carried over from photography, of capturing his human subjects at just the right moment - the young girl on the swing is the best example here.

But it is the final image of each cycle, the watery “z” counterpoint to the fiery “y”, that I find I now carry around in me like the prayers that J.D. Salinger’s heroine Franny Glass hoped to utter under her breath incessantly. It is a shot of an ocean wave, sunlight gleaming down upon it, breaking… backwards. Like the catching of one’s breath, like a rewind to the beginning, for a second I am “borne back ceaselessly into the past.” And then, the game is afoot. The film has yet to unfold. The equation remains unsolved.

Next time: So while you sit back and wonder why, I got this fucking thorn in my side. DVD Spine #100