|

|

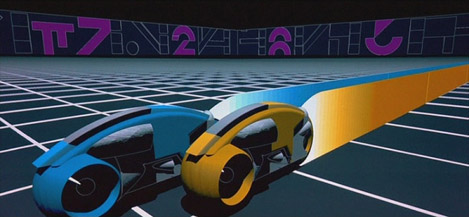

Viking Night: TronBy Bruce HallAugust 31, 2010

Director Steven Lisberger and producer Donald Kushner tried very sincerely to create something primarily about overcoming tyranny – the cutting edge special effects were viewed simply as a natural extension of the message they were trying to convey. But the film’s philosophical underpinnings are too often sabotaged by some laughably poor dialogue and an almost nonexistent level of character development. Like any film this one has its share of weaknesses, and if you wanted to dwell on them you could levy any number of additional criticisms against it. If Dillinger was smart enough to create a super intelligent AI powerful enough to take over the world, why did he need to steal ideas from Flynn to get ahead? If Encom was such a bad place to work, couldn’t everyone have just taken their big brains over to Microsoft? And despite its generally likeable cast, the film’s performances are merely serviceable, if little more. Jeff Bridges brings his trademark anarchic flair to Flynn which is good, because the script gives him little to go on. Bruce Boxleitner was reportedly a little uncomfortable with the material and if true, it shows in his performance. But Alan’s inherent skepticism serves as a convincing foil to Flynn’s paranoid bluster – the contrast of personality actually ends up working fairly well. Master Thespian David Warner is probably the standout, as he gets to play three roles here and they’re all the sort of diabolically evil bastard that every actor dreams of playing at least once. Tron has its flaws to be sure, but as an experiment in flirting with the impossible it succeeds brilliantly. What audiences saw up on the screen in 1982 was something they’d never seen before and really have never seen again – it was a once in a lifetime experience that was special primarily by virtue of being unprecedented.

|

|

|

|

|

Friday, November 1, 2024

© 2024 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.