Chapter Two:

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse

By Brett Beach

January 6, 2011

I am embarrassed to admit the extent of this avoidance of Lang’s films was so complete that I did not even know the proper pronunciation of his master criminal’s last name. I had presumed it was Mah-byoos, to rhyme with abuse and, if one considered it as an inside joke in broken French: m’abuse, or I abuse myself. Since the first film has intertitles only, and no spoken aloud dialogue, it wasn’t until halfway through The Testament of Dr. Mabuse that I could hear it properly delivered as Mah-boo-say. This is humorous and it must be said, more than a little ironic.

Mabuse’s name, its invocation, and the secret (or lack thereof) of his identity are actually turning points in both of the first two films, with the former almost a subtle running gag. People are forever on the verge of uttering his name aloud to make the identification that he is the villain in question, only to be silenced, either by forces wrought by Mabuse’s control (a city full of organized henchman as adept with vintage pistols as they are with exploding drum cans) or beyond the control of the individuals themselves (mind-control and manipulation or paranoia that easily slides into full-tilt madness).

Mabuse hides in plain sight in the first film, as a respected lecturer and psychiatrist who involves himself in the lives of those he corrupts and ruins, while also disappearing behind an endless array of quite genius disguises as he determinedly works his destruction in the stock markets, gambling dens, and music halls of his city. Mabuse lurks in the darkness in the second film, mute from madness, he is presumed to be incapable of menace from behind the walls of the mental institute that has been his home for over ten years. And yet, he exerts his psychic power over those who think they control him and ultimately appears to carry out his grand design from beyond the grave. Depending on how you take the meaning of the word Testament, you could conclude that this was a triumph of the “will” equal to the real-life one documented by Leni Riefenstahl 2 years later.

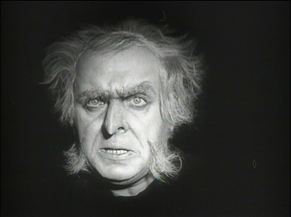

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is not only a sequel to the events in Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, but contains a running commentary on the phenomenon of the Mabuse figure himself. Lang, working as he did on the first-go-round from a script by his wife Thea von Harbou, does so in a winking manner early on, as a room full of graduate students, who perhaps only know the name of Mabuse as a whispered-about bogeyman from their not-so-distant childhoods, collectively recoil in horror when shown a slide of Mabuse by their professor Dr. Baum, who also oversees Mabuse’s daily routine.

With his electro-shock white hair and accusing gargoyle features, Mabuse (played once again by the indispensable Rudolf Klein-Rogge) casts an imposing shadow over the film, even though his on-screen time is well under 10 minutes of the two-hour length and his voice is featured for even a shorter amount of time. In a brilliant narrative decision that only becomes apparent in retrospect (or if you have been fortunate enough to read well-argued analysis in advance of seeing the film), Mabuse is never seen AND heard at the same time.

Continued:

1

2

3

4

|

|

|

|

![]() Tweet

Tweet

![]() Print this column

Print this column