Chapter Two: The Color of Money

By Brett Beach

May 12, 2011

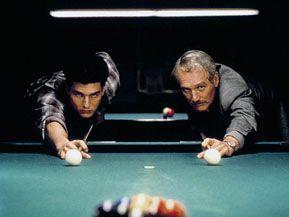

The Color of Money is also the start of Cruise’s mini-film career of playing the mentee to an older and (supposedly) wiser male figure who helps him to see the error of his cocky ways and/or gain a measure of maturity (see Cocktail, Rain Man, Days of Thunder, The Firm). Visually, this is aided and abetted by the fact that although it was filmed immediately after Top Gun wrapped, The Color of Money somehow showcases a Cruise who seems both impossibly young, and younger-looking than Pete Mitchell (I think it’s because he’s out of the military duds and flashing those pearly whites every 30 seconds).

From the opening scene until the very finish, The Color of Money forces the audience to consider Vincent Lauria in the context of Fast Eddie. We can see Vincent in the background behind Fast Eddie at the bar even before the latter really becomes aware of him, and reminded of him at that age. The advertising and poster art for the film drive home the point that Vincent is an heir apparent to “the hustler” but the film really doesn’t. Aside from a few vague references, there are no plot shout-outs to The Hustler. Fast Eddie could be any aging once-upon-a-time big shot with an eye for talent and a rediscovered lust for the action. It’s both a wise move on the film’s part (I would be curious to know what portion of the initial audience was aware of and/or had seen The Hustler) and a bold move that doesn’t quite pay off.

Despite a screenplay by crime writer Richard Price, The Color of Money doesn’t have much of an air of that genre, or any genre for that matter. While the original played out with an air of tragedy and the slightest tastes of the unsavory, its follow-up is an unapologetically commercial entertainment that electrifies in individual moments but is relatively shapeless in form and plot. It flirts with being a buddy comedy-drama, a road movie, and a tale of redemption, but it never quite commits strongly enough to any of those. There is an unexpected twist right near the very end that sets up what promises to be a climactic showdown, before the story sidles off into an ending that is as deliciously unresolved and open-ended (although completely polar in tone) as that of The Hustler.

In Martin Scorsese’s long and winding oeuvre, The Color of Money is an oddity in several ways. It was his biggest commercial hit by far of the 1970s and 1980s. It came in the midst of his stretch to find other projects, post-Raging Bull, to keep him occupied while attempting to get The Last Temptation of Christ off the ground. This creative meandering resulted in a black comic take on Taxi Driver (The King of Comedy), a Kafkaesque nightmare comedy (After Hours, my favorite Scorsese film), an episode of Amazing Stories and the video for Michael Jackson’s “Bad”.

The Color of Money has the design and shell of a Scorsese, but thematically feels very lightweight. It is first and foremost a sports picture, and in its rendering of the electric charge in the air that can accompany a tight game of nine-ball, it succeeds at finding a way for the crisp and vibrant color cinematography to compete with the haunted blacks, whites, and grays of The Hustler. Odd or not, it most reminds me of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Scorsese's 1974 follow-up to Mean Streets that shares the entertainment value of The Color of Money, and is a film more concerned with relatively low-stakes character arcs than plot antics.

While Vincent seems to be an open book, both Fast Eddie and Vincent’s girlfriend, Carmen, remain at times maddeningly opaque in regards to their motives. This is the bold move I referenced earlier. The plot may be relatively straightforward, but courtesy of Price’s dialogue, they are able to speak around their feelings. Both of them may only be using Vincent to take them as far as he can, but they also care for him on some level as a son figure and a lover, respectively. Newman provides strong combustion with actress Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio (who, it is worth reminding, also snagged a nomination for her work) and it is a pleasant upending of clichés that they don’t wind up sleeping together.

This disconnect between the Fast Eddie that we might remember or expect and the one on-screen is what keeps the film emotionally at bay for me. Newman’s performance is solid but he doesn’t seem like Fast Eddie 25 years on. He is charming and spry, and leveled with just the right touch of gravitas, but he never seems haunted enough. It becomes apparent early on that the character of Fast Eddie is simply being shoehorned into a tale where he doesn’t really belong and where he has to play second banana. This doesn’t render The Color of Money a loss, but, as typified by the generic Robbie Robertson and Don Henley-driven 1980s score and soundtrack, it makes it more a product of its time than something with the power to become timeless.

Continued:

1

2

3

|

|

|

|