|

|

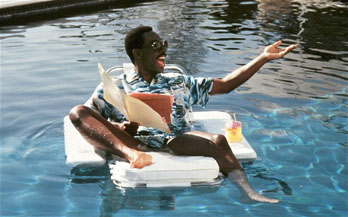

Chapter Two: Beverly Hills Cop IIBy Brett Ballard-BeachAugust 30, 2012

Bruce Willis was never more disheveled (while still sporting a full head of hair) than as disgraced Secret Service agent turned low rent private dick Joe Hallenbeck, whose signature moments are fishing someone else’s still smoldering cigarette out of the gutter to save on buying a new pack, and punching a hood so hard in the nose it drops him dead on the spot. As he wends his way through a convoluted plot involving blackmail, political corruption, and an attempt to legalize sports gambling, he picks up an unwanted sidekick, a disgraced quarterback (Wayans) whose girlfriend has been murdered, attempts to resolve issues of marital infidelity with his wife and connect with his mouthy and emotionally distant daughter, and tangles with a seemingly endless menagerie of chatty, homicidally inclined henchman - wonderfully embodied by the likes of Badja Djola, Kim Coates and Taylor Negron, the latter channeling Martin Landau’s character from North by Northwest - who wind up stabbed, shot, set on fire, exploded and stabbed/shot/eviscerated by helicopter blades. There is no top that isn’t eventually gone over. My favorite shot is a perfectly framed moment of an upside down car crash landing into an aghast mansion dweller’s pool. It’s the excess of the entire film distilled into three seconds. Elsewhere, the opening credits sequence - a slick production video for “Friday Night’s a Great Time for Football” sung by Bill Medley (from The Righteous Brothers) is filled with enough patriotic jingo to qualify as a lost image from the Parallax Corporation’s assassin screening test. It’s so effectively blunt in aping the real thing that its comic and satirical nuances may not be fully appreciated.

|

|

|

|

|

Friday, November 1, 2024

© 2024 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.