Mythology

Rules of Reality

By Martin Felipe

July 2, 2009

A few weeks back I wrote about the return of Futurama on Comedy Central and how it and other animated series are what have come to be called "mythology shows". Traditionally, that term represents a sci-fi or fantasy program, usually serialized. The label came into common use in the 1990s when the X-Files unspooled their alien conspiracy over the course of nine seasons. As we enter the deep days of summer and new television offerings become sparse, I started to consider where to draw the line. What is a mythology show and what isn't? Most of summer's offerings aren't really in the same ballpark as The X-Files or other shows which have earned the mythology moniker. Does the story of a pot dealing housewife count? How about that of a fired spy in Miami? Or a house of firefighters in New York?

For that matter, why the term "mythology" in the first place? Are we talking Campbell's hero's journey here? What about the standard archetypes? Or is it more about morality tales? I think dribs and drabs of all the different interpretations of the word apply here, but I don't think any of the more academic connotations of the word are really definitive. When we discuss a show's mythology, I think we're really talking about the world in which the characters inhabit, and the rules by which the world operates.

This is a fairly clear approach when we're dealing with fictional settings like that of Lost's island, or Buffy's Sunnydale. They may be fantasy based, but no, anything doesn't go. There are protocols that must be followed as in the real world. A vampire on Buffy, for example, has different rules to (un)live by than those of True Blood. True Blood's vampires can exist in the sun for extended periods of time while sustaining great damage. Buffy's vamps, on the other hand, have about five seconds of exposure before turning to dust. There are simple, established ground rules by which our characters must live. If a Buffy vampire lasts long in sunlight, there had better be an intertextual explanation.

It may seem obvious to say, but I don't think we can exclude these standards for a real world setting, either. Yes, Tommy Gavin and his crew continue to fight fires in a post 9/11 New York, a setting of what seems to be the upmost verisimilitude, but this verisimilitude would be destroyed if there were to be an appearance by a vampire or a vampire slayer. We accept fantasy creatures in Sunnydale because Joss Whedon clearly establishes the rules of Sunnydale, then plays within them. If there is a seemingly supernatural event on Rescue Me, there needs to be an explanation for it that works within the rules of its established world. If Tommy sees ghosts, he's just seeing things, they're not really ghosts. If Garrity starts singing as if in a musical, it's just a drug-induced hallucination.

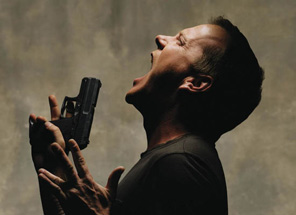

But even shows set in what seem to be reality apply some rules early on to establish some exaggeration of that reality. The dialogue on Rescue Me has a rhythm, a sing-song wit that any single real-life person would have a difficult time maintaining, let alone a whole group, trading off quips, topping one another as if the very dialogue belonged in one of Garrity's imagined musical sequences. The West Wing has a similar exaggerated voice. The stories take place in the White House, but the characters speak with an almost Shakespearean meter based on repetition and measure. It's not only the dialogue in a real-world show, either. Jack Bauer must have access to some mystical freeway called Route 24 considering how quickly he gets around the infamously congested streets of Los Angeles.

The reason these exaggerated conventions work is that they're grounded in some authenticity, an anchor for us to cling to when the creators push that reality. And this goes for Bauer's super speed as well as for Lost's smoke monster. Because so much of 24 is true to life, when Bauer does get from Burbank to Santa Monica in five minutes, we forgive it. On Lost, our characters discover the fantastic events and properties of the island along with us. Their reactions make the fiction palatable to us. But, on both shows, once the universe - whether mostly real or mostly imagined - is laid out for us, then that's where the characters will be playing. It's no fair switching it up down the line.

The rules are real for the most part on a Rescue Me or a 24, and extreme on a Lost or a Buffy, but what it boils down to is that the viewers want to see these characters inhabit this same world week after week, as long as the creators don't betray the rules they have established. We learn these rules as viewers and come to derive pleasure from seeing where the characters can go within them. And we don't want these rules broken. It's like a contract between viewer and show runner. When the contract seems to break, we start to feel betrayed. In the hands of a good artist, we will always return to that world, with the rules intact, even if they've toyed with us for a bit. What I guess I'm saying is that all good shows, true to life or fantasy, are mythology shows.

|

|

|

|