|

|

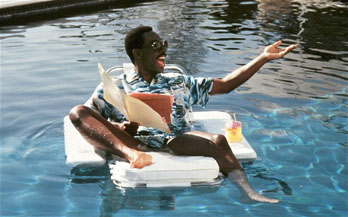

Chapter Two: Beverly Hills Cop IIBy Brett Ballard-BeachAugust 30, 2012

And as is so often the case, that “general consensus” consists of surface appearances alone (which might be an appropriate allegory for someone who worked with producers Don Simpson and/or Jerry Bruckheimer on over 1/3 of his oeuvre). Aside from his first film being a horror film, all of his other features might best be described, retrospectively, as Tony Scott action films. His biggest financial successes came very near the beginning of his career (back to back with 1986’s Top Gun and 1987’s Beverly Hills Cop II) but his smaller successes and even his commercial “busts” (his debut with 1983’s The Hunger, 1990’s Revenge, 1993’s True Romance, 2005’s Domino) are perhaps a better evocation of his strengths and trademarks: the ability to craft live-action cartoons that paradoxically possessed emotional resonance; fragmented hyperkinetic editing that could become viscerally wearying or punishing but that seemed necessary to capture his protagonists’ frequently upended lives , jittery nerves and tortured below the skin psyches (re: his four collaborations with Denzel Washington in the ‘00s), and ensemble casts that centered around a big name or two but that often allowed bit parts to make an impression, often in only a few minutes, even in the midst of all the sound and fury. The portrait that emerged in the pieces of praise and memoriam over the last week painted a picture of a larger than life figure, very nearly a caricature (who might be at home in one of his own features), but one who was generous with his success and with his on-set collaboration. Clad in an always present pink t-shirt and pink baseball cap, with a history of speed-car racing, bare hand rock climbing, and chomping stogies for breakfast, he looked like Lawrence Tierney’s more chipper brother and seemed as if he would have been at home grappling with Ernest Hemingway (if not the man, if not the myth, then at least the serenely machismo portrait on display in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

|

|

|

|

|

Friday, November 1, 2024

© 2024 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.