|

|

Movie Review - Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of GrindelwaldBy Ben GruchowDecember 17, 2018

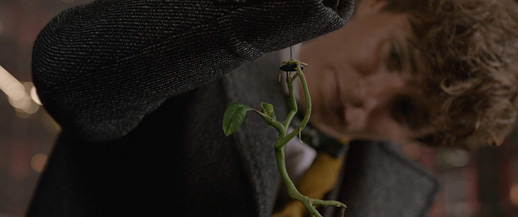

The obvious answer, I know, is that without the search-and-recruit scenario, we would be deprived of Newt’s interaction with Dumbledore, with intermittent love interest Leta Lestrange (Zoë Kravitz)—or much of a reason for Newt to be a part of the proceedings at all. Certainly his own quest, in which he attempts to track down ex-Auror and other intermittent love interest Tina Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), is a threadbare narrative that seemingly exists to pad time in between Grindelwald-related exposition dumps. Scenes with Tina’s sister Queenie (Alison Sudol) and Jacob Kowalsky (Dan Fogler) are more threadbare still; it is a sign of the movie’s spinning narrative compass that the character development with these latter two is more ostensibly transformative than anything that happens between Newt and Tina, which we don’t care about, and yet it occupies what feels like a quarter of the screen time. And we haven’t even gotten to Grindelwald’s master plan. Or the beasts. None of these dissociated story threads really go together, either, and so the net effect is a movie that starts and stops and hitches and clunks along and never once feels like it’s actually building to anything. There’s no sense of momentum. Although I remember certain moments and visuals, I could not tell you what order they go in to save my life. The dialogue does the movie no favors, either. Absent an errant line here or there that actually achieves the effect it sets out to—and Depp, giving one of the two good performances on offer here, performs the hell out of a late monologue that briefly brings the movie’s character and narrative conflict into sharper focus than it earns—this is a film populated by adults that articulates philosophy and emotion at the basic level of a teen sci-fi novel. It’s below anything in the previous film. And it’s a waste of a talented cast; nobody here apart from Depp and Law as Dumbledore is really trying except for the big moments, but those big moments really underscore how chaotically malnourished everything leading up to them is. I’m thinking of a scene where a major character walks through fire (of a sort) and the evident physical agony on display is like a beacon to us in the audience, reminding us that we should be feeling something for the individual in question and that we are not. The technical credits are less offensive…but that’s really just a way of saying that it’s in focus the whole time, and that the effects artists remembered to paint out all of the digital backdrops. There are exceptions (the Niffler, a little creature that looks like a cross between a platypus and a penguin, remains an entertaining personality; there’s a giant mythical feline-dragon hybrid so energetic in its movement and expression that it utterly dominates every shot it’s in), but Crimes of Grindelwald is less a piece of evocative visual storytelling (a claim its predecessor could make) than an endless series of muddy and indistinct compositions, depicting incidents of sluggish energy, until they finally give way to sound and light in the final act. The way that final act is carried off reminds me of another big young-adult film franchise: those blasted Twilight movies that consumed the moviegoing consciousness for a few years around 2010. Those also consisted mostly of shapeless masses of non-incident and poorly-acted dialogue, with all of the explicated conflict and rising action and climax packed into the final twenty minutes. Grindelwald isn’t quite that backloaded, but it’s playing in the same ballpark, and the the light-show battle over Paris that marks the movie’s end seemingly makes up the rules as it goes along. Meanwhile, the movie’s final scenes are notable mostly for how destructively they retcon the parent series, in a transparent bid to give this one some stakes and a reason to exist. By this point, I’m thinking: There are still three more Fantastic Beastses yet to come. The tagline on this movie’s poster reads like a desperate plea for inspiration from the filmmakers. 1.5 out of 5

|

|

|

|

|

Thursday, October 31, 2024

© 2024 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.