By Alex Hudson

June 3, 2002

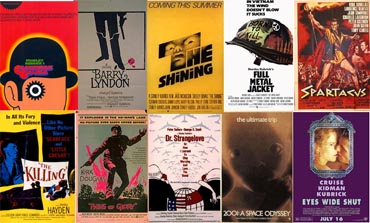

He revolutionized the science-fiction genre. He made a Cold War satire at the height of the Cold War. He created a camera lens capable of filming entire scenes via candlelight. He was an independent filmmaker before independent filmmakers existed. He imploded cinema. He was Stanley Kubrick.

There's a point midway through Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey when resident supercomputer HAL 9000 has pinned and trapped the last surviving astronaut, Dave Bowman, in a space pod outside the Discovery spaceship, leaving the shocked and betrayed spaceman isolated and alone in the haunting emptiness of space to face a near-certain death. The stunned Bowman, confined to his tiny pod, pleads for his life, realizes that his pleas are futile, and stops. It is this moment, this precise moment, that Dave Bowman - and Kubrick, and his audience by extension - tastes the infinite, feels the nothingness, looks squarely into the eyes of the abyss, and stands firm, unafraid.

Self-Made

Kubrick's two loves as a late adolescent - chess and photography - would instill and ingrain the fundamental traits that Kubrick would later employ in making films. Photography taught Kubrick how to compose, frame, layer images. Chess taught Kubrick how to think in advance, how to plan movements based on the value of time and how to orchestrate a winning stratagem.

Three short films and two warm-up feature films were all the Bronx-born son of a doctor needed to reach the point of total command of the filmmaking craft. Unlike his peers, who were reared and instructed by the studios on "how to make a film," Kubrick learned how to make a film - to write, direct, edit and do virtually every other aspect required to make a film - on his own.

Masterpiece Maker

Making a film is difficult. Making a good film is nearly impossible. Making a masterpiece is either a fluke or the calculated result of the intense concentration of genius. Making a string of masterpieces - as Stanley Kubrick did - is a sign of sheer brilliance, extreme discipline and a touch of the divine.

Kubrick's first masterpiece was The Killing. An overlooked noir, The Killing marked many Kubrick firsts. It was his first feature with a budget. It was his first film with professional actors. It was his first studio film. The Killing is the carefully-told story of the planning, orchestration and aftermath of a robbery of a racetrack.

A director's protagonist is an extension of the director. Whether the director actually writes or creates the character is irrelevant. What matters is that a director is attracted to protagonists who generally share similar traits, and who experience similar trajectories, similarities of character and experience that speak to the director. Kubrick's first true protagonist, Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden), is a rebellious outsider, a criminal mastermind who plots the racetrack heist down to the smallest detail. The parallels between Johnny Clay and Kubrick are clear; both operate on precise, thorough master plans which require exacting attention to detail and total cooperation from a team of players with specific roles.

I Am Spartacus

Leaving noir with a new high watermark, Kubrick turned his attention to the war picture. Paths of Glory, the searing Humphrey Cobb anti-war novel, had fascinated Kubrick as a youth. No less fascinated with the material as an adult, Kubrick convinced Kirk Douglas, who was impressed with The Killing, to star in the picture, and with the Douglas name, secured a studio's willingness to fund the film (United Artists, teaming with Douglas' own production company, Bryna, and Kubrick's Harris-Kubrick Productions).

Paths of Glory is a viscerally-charged, high-intensity war film that refuses to waste screen-time on perfunctory action scenes and the generic cross-ethnic brand of wily war-torn characters. Instead, Paths of Glory is the anti-anti-war film. Unrelenting, Paths of Glory does to the war film what The Killing had done to noir; it stripped the genre film to its dramatic core, eliminating the conventional and leaving the unconventional.

Audiences, critics and the film world took notice. Such was the potency of Paths of Glory that France banned the film for several decades, partly due to Kubrick's negative portrayal of the French army - how dare he? - and partly due to the harshness of Kubrick's representation of the state and military institutions. This unblinkingly contemptuous representation is ingeniously realized in Kubrick's juxtaposition between orderly static shots of the sterile and ordered world of the generals and chaotic, handheld shots of the barbaric and chaotic world of the soldiers.

Although the Kirk Douglas and Stanley Kubrick collaboration on Paths of Glory was not completely harmonious, Douglas hired Kubrick two years later, as a replacement to the dethroned Anthony Mann, as director of the massive-budgeted Spartacus. Kubrick was merely a hired hand on Spartacus, and his hands were tied at that. Despite the clash of egos - Kubrick begged to make the action more action-full and the script less dim-witted but Douglas, again financing a project with his own money, allowed only one of those things to happen - Spartacus is nonetheless one of the most compelling historical epics.

Kubrick's habit of leaving a genre with a new benchmark remained unscathed, albeit barely. The impact of Kirk Douglas cannot go unmentioned here. Douglas routinely appeared in directors' bleakest, career-defining work throughout the '50s and early '60s. Billy Wilder, Vincente Minnelli, John Sturges, Kubrick; they all used Kirk Douglas as a sort of mercenary, macho mouthpiece. He's a proximity of masculinity that these directors aspired towards, and he could be inserted into extreme roles that celebrated men at their best and condemned men at their worst.

Dark, Apocalyptic Comedy

Great directors redefine genres. God-like directors create genres. With Lolita, and then Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Kubrick made the dark comedy a viable genre option. Crippled by dying, but still stringent, morality codes, Kubrick was forced to turn the risqué Lolita into an (almost) over-the-top dark comedy, using double entendres and visual gags to replace the blatant sexuality of the source material. Filmed in England ostensibly because production costs were lower, the true impetus behind Kubrick's move was his desire to distance himself from Hollywood; its formulaic, cookie-cutter films, its group-think, its mediocrity.

Effective or not, Lolita ushered in the dark comedy. It certainly wasn't the first dark comedy, but it was one of the earlier sexual dark comedies, and it paved the way for Kubrick's own follow-up, Dr. Strangelove. Based on the dramatic Peter George novel, Red Alert, Dr. Strangelove tells of the accidental triggering of a nuclear strike by the US against Russia. Kubrick replaces the serious-minded Kirk Douglas with the comedic-minded Peter Sellers as his new protagonist protégé; Sellers played an assortment of characters in Lolita and he played three distinct characters in Dr. Strangelove: The title character, the President of the United States Merkin Muffley, and Group Commander Lionel Mandrake.

From the opening scene, behind the romantic chords of Try a Little Tenderness, where we see a B-52 SAC nuclear bomber refuel mid-air (read: aerially copulate) with a tanker aircraft, Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove is a series of overt references and allusions to sex: Character names, contamination of precious bodily fluids, copulating planes; Kubrick reduces nuclear holocaust to sexual humor.

HAL 9000

With five consecutive successful - critically or commercially or both - genre films, Stanley Kubrick had earned unprecedented control and with it the rare freedom to experiment. Begun in 1965, 2001: A Space Odyssey is one of the most singularly ambitious, technologically innovative and narratively implosive films ever made. The virtues of the film spurred scholarly studies, books, movies, but what ultimately matters about 2001 is that it is the brainchild of an artist teeming with ideas, an artist overflowing with creativity and an artist heralding to the world his genius.

2001 is an experience. For some, a tedious one; for others, an inspirational, powerful and enlightening glimpse of what art at its most daring is capable. Above all, 2001 is the crystallization of the Kubrickian worldview. Free of studio constraints, Kubrick poured his mind and heart into making not only the definitive science-fiction film, but finally articulating, however abstractly and ambiguously, his praise, contempt, and aspirations for humanity. In 2001, man has enslaved himself, consciously handing the reigns to computers. HAL 9000, not Dave Bowman, is the central character of 2001; he's cautionary tale, dramatic focal-point, Cyclops of the odyssey, and man's worst nightmare, all at once.

Anti-Hero

A Clockwork Orange details earthbound life possibly as the events central in 2001 occur. Whereas life in space is monotonous, life on Earth is anything but. Alex DeLarge (played with earnest zeal by a codpiece-wearing and fake eyelash-sporting Malcolm McDowell) is a fun-loving, Beethoven enthusiast who also happens to partake in gang rape, brutalizing decrepit homeless people and all things thuggery.

The Kubrick protagonist has reached the most unredeemable stage. Whereas all Kubrick heroes up to this point - Johnny Clay, Colonel Dax, Spartacus, Humbert Humbert, HAL 9000 - are anti-heroes presented as flawed human beings (or machines), they all had a functioning moral compass. With Alex DeLarge, a creation of writer Anthony Burgess, that moral compass is broken. As Kubrick is progressively heightening his reputation, his protagonist is progressively amplifying his wrongdoing. The hard-earned freedom Kubrick strived for, and achieved, materialized in the Kubrick protagonist becoming as loathsomely likeable as possible.

A Clockwork Orange is a triumph of virtuoso filmmaking. The camerawork, lighting, music, sets - everything - are as if God himself has decided to bestow the world with a perfectly-made film. As he did with 2001, Kubrick made the unconventional decision to use a score consisting mostly of classical pieces (in addition to the strikingly-original synth-electronic music created by Walter/Wendy Carlos). Kubrick's futuristic dystopia is at once full of beauty and horror, gorgeousness and heinousness, good and evil. The story posits the question of which is worse: To do wrong, or to be unable to choose whether to do wrong.

Visual Poetry

With A Clockwork Orange, and 2001 before it, and Barry Lyndon after it, Kubrick has attained a triumvirate of films of unspeakable visual poetry and complete narrative bliss, works that rival any other director's best threesome. Barry Lyndon unfolds as a ridiculously picturesque, seductively intoxicating, languid dream. Stunning visual after stunning visual, Barry Lyndon accounts the life of one Barry Lyndon, a roguish social-climber in 18th century Europe.

Again, the Kubrick protagonist is simultaneously likeable and unlikable. Again, the Kubrick protagonist is a rebel trying to achieve societally acceptable goals by non-societally acceptable means. A metaphor for filmmaking and art-making, the Kubrick protagonist perpetually strives for purpose, grasps for meaning and refuses to allow the establishment to have any role in the process.

The End

Making just three films in two decades to conclude his prolific career, Kubrick defied expectation to the end. With The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and, finally, Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick gave us Jack Torrance, a writer-turned-killer in the isolation of the Overlook Hotel; Private Joker, a marine-turned-killer in the chaos of Vietnam; and Dr. Bill Harford, a doctor-turned-zombie in the streets of pseudo-New York. Well-made films all, they vary in effectiveness and potency. Still, like all the best directors, even at his worst, Kubrick was better than the rest.

There are various measures of the impact of a great director. His number of masterpieces, the consistency of his output, his contributions to cinema, whether his work stands the test of time - in each of these qualifications, Kubrick excelled. With unprecedented consistency, Kubrick left the final word in the noir, the war picture, the historical epic, the dark comedy, the science-fiction film, and the horror thriller. But more than simply operating within the constraints of specific genres, Kubrick pushed forth and liberated film from these constraints, and plunged narrative filmmaking into a stratum few other filmmakers had risked to take it.

The Stanley Kubrick Production is timeless. His work will usher film into the minds of generations of future film watchers and film makers. Stanley Kubrick was a visionary in the truest sense of the word. He gave us man on the moon before man reached the moon. He gave us art undiluted by trends, untouched by studio bosses, unwaveringly difficult and complex. He gave us HAL 9000 and Spartacus, Barry Lyndon and Dr. Strangelove, Jack Torrance and Private Joker. He gave us art.

View other columns by Alex Hudson