|

Millennium MamboBy Chris HydeMarch 8, 2004

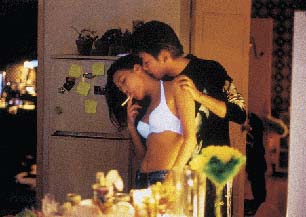

After a long wait, master storyteller Hou Hsiao-hsien's Millennium Mambo makes it to a handful of screens in North America. Distributor Palm Pictures has proven to be one of the most daring of American film operations, both in their theatrical releases and with their DVD lineup. This outfit has shown a willingness to gamble on properties such as Lynne Ramsey's Morvern Callar, Olivier Assayas' demonlover, and the Pang Brothers' The Eye, as well as releasing compilations of the videos, commercials and short films of artists like Michel Gondry, Spike Jonze and Chris Cunningham. With the release of Millennium Mambo, the operation now turns their eyes towards Taiwan and gives domestic viewers the chance to see the latest film by one of the world's great working directors. Filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien has helmed some 15 films in the course of his career, with the critical consensus being that the 1993 The Puppetmaster and the 1998 Flowers of Shanghai are his two top offerings thus far. This latter film is especially engaging, a rumination on sex and power set in the brothels of 1880s Shanghai that proved to be one of the most arresting films made anywhere in the world during the 1990s. Hou's newest movie doesn't quite attain the heights of his best previous efforts, but there's still plenty of value here that makes this piece of celluloid well worth a long look. The surface story for this one involves Shu Qi as an aimless Taiwanese youth bouncing around turn of the century Taiwan under the watchful eye of her crack smoking boyfriend and some other disreputable acquaintances. Much of the film is played out to a thumping techno beat as the striking beauty of the film's star floats through the flickering neon of a modern urban setting with its lurking air of violent menace. But the director doesn't tell his tale in a straightforward and naturalistic manner; instead he uses a distancing narrative voiceover and a storytelling conceit that sets some of the tale ten years into the future to frame the film's actions. These aspects help give Millennium Mambo a disconnected feel that reflects the disaffected emotions of its characters as well as allowing Hou to play masterfully with the way that time is presented to the audience. This is often reminiscent of the manner in which recent cinema by artists like Assayas, David Lynch and Bela Tarr have dealt with the notion of time passing onscreen, though Hou is enough of an original that the way that this is handled remains entirely his own. Viewers of an impatient bent should go into this one well warned that the director's approach is more or less the complete antithesis of the quick cutting style that marks most of today's mainstream pictures. Long, languorous takes that follow characters for lengthy periods of time are not at all uncommon, and anyone who isn't captivated by Hou's mode of presenting a story may very well find themselves utterly bored by it all. On the other hand, the immersion allowed by this technique allows an examination of the emotional state of the film's lead actress that wouldn't be possible in a more heavily edited form. The extended takes let the drifting camerawork linger over Shu Qi's Vicki and her cohorts, gently probing the smoky haze of their environs with its unmoored and dissociative gaze. As nearly every scene in the film centers directly on the character that Shu Qi plays, it's nice to see that her dramatic work here looking better than it ever has. While it's impossible to deny the former softcore starlet's stunning looks, this writer has always found her acting to be a bit lacking and often uneven in her previous roles. The pedestrian performance that she turned in recently on the entertaining Charlie's Angels ripoff So Close was fairly disappointing, and though I enjoyed her hilarious cameo in Just One Look there was really very little for her to do there. (It's also fun to speculate on just how different Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon might been if the actress hadn't ducked out on playing the part that eventually went to Zhang Ziyi). But here she is in fact quite excellent, delivering a nuanced and emotional performance that gives the movie a true center and evinces a depth that I'll admit I didn't think that she was capable of expressing. Perhaps there truly is more to Shu Qi than what meets the eye; and if the skill on display here is any indication, then maybe we can expect more from her in the future than the inherent star power that she undoubtedly possesses. In addition to Hou Hsiao-hsien's amazing directorial skill and the improved acting ability of the film's star, Millennium Mambo comes with one last aspect that recommends it: brilliant cinematography by Mark Ping-bin Lee. This cameraman has shot many of Hou's films, and additionally has worked for great directors like Wong Kar-wai, Tran Anh Hung and Tian Zhuangzhuang in the past few years. In this one, his photography is a colorful and leisurely evocation of Vicky and the apartments and clubs that she wends her way through. The artful manner that Lee uses to shoot the action results in a removed but beautifully blurred multihued portrait, a shimmering picture of light and dark that swirls with life. It's simply the perfect accompaniment to the measured editing rhythm employed by the director to tell his tale of Taiwanese angst, and it's obvious that there's a reason these two great artists have been teaming up for over 15 years. All in all, while Millennium Mambo may perhaps remain a cut below Hou Hsiao- hsien's best, even a slightly lesser Hou effort is better than most other directors' top output. Viewers willing to give themselves over to the languid pace of the film will find a movie suffused with an air of disconnected sadness and intriguing expression, in addition to a freefloating sense of time. One of the filmmaker's greatest assets as an artist is his ability to reflect simultaneously on his characters and his art, the work standing both as story in its own right and as a deliberation on the act of making movies. Hou's pensive and thoughtful films often recur thematically on this point of contemplation about art and the artist, lending a depth of complexity that few filmmakers active today are capable of handling in a subtle enough way so as to be effective. Every single film by this Taiwanese master is in some way a revelation, and this newest bit of cinema is in no way an exception to that rule. Let's just hope that for the next one we won't have to wait three full years for a domestic release.

|

Thursday, January 08, 2026

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.