|

Valerie and Her Week of WondersBy Chris HydeFebruary 3, 2004

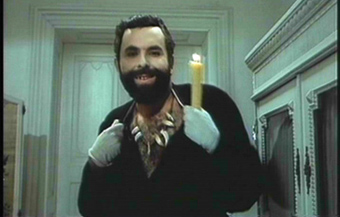

Jaromir Jires' shimmering Czech coming-of-age classic reappears three decades after its creation. The Czech film industry has a lengthy history, stretching as far back as the 1890s when the first films were made in what was then called Bohemia. The country's most fervent celluloid flowering took place in the early-to-mid 1960s, when filmmakers such as Milos Forman, Elmar Klos, Jan Kadar and Jiri Menzel took advantage of a rarefied cultural atmosphere to create work worthy of international recognition. In fact, in 1965 and 1967 two Czech films (The Shop on Main Street and Closely Watched Trains) won Academy Awards, with Loves of a Blonde garnering its own nomination in between in 1966. Unfortunately, the USSR's 1968 invasion of this eastern European country had a deleterious effect on all the arts there, with cinema especially feeling the crushing weight of Soviet censorship. Leonid Brezhnev and company didn't manage to completely stamp out creative filmmaking there, though of necessity much of the post-invasion output was much more fantastic and allegorical in nature than before. A prime example of that phenomenon is Jaromir Jires' artistic and strange story of a young girl's sensual awakening, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. Not seen much in the United States over the last three decades, this unique film has now come back both in celluloid and in a new DVD from Facets. This reviewer has seen only the new 35mm print screened as part of the traveling Czech Horror and Fantasy Festival that is making the rounds, so I can't comment on the quality of the digital version here. The film version is beautifully restored, however, so if the same source materials were used for the disk then its colorful, almost softcore feel should have translated just fine into the new medium. The plot of this heavily symbolic, sometimes surrealist piece is rather difficult to sum up in a brief way. A young female (Jaroslava Schallerova) is introduced at the opening as she drinks from a burbling fountain, gobbles ripe red cherries and enjoys the wafting aroma of the flowers of the land. Though nubile, it's clear from the first that this fair maiden is bursting with sensuality, poised on the edge of womanhood. As the camera follows her through her day-to-day life we meet the principals who fill her life: her stern, pallid grandmother, a boy who may or may not be her brother, and the vampirish constable of the town whose relation to Valerie may in fact be paternal. What passes for a plot here mainly centers around a pair of magical earrings that Valerie has inherited from her no longer extant mother. What sort of power these talismans hold is unclear, though the ringing sonic signature that accompanies their appearance onscreen (which to these ears was painfully similar to a game show chime) certainly is meant to point up their significance. Valerie's grandmother tells her to throw away the baubles as they will cause her naught but pain; her "brother," on the other hand, insists that their magic is protective and that the cruel cop seeks to steal them so as to prolong his zombified life. But the overt fairy tale nature of this film comes quickly to the fore when the earrings are stolen from Valerie's possession on the very day that she experiences her first menstruation; following these nearly simultaneous incidents, the girl-now-turned-woman finds herself exposed to all the desirous machinations of the adult world, with her youthful naivete sent spinning away into the past. Much of the film's attraction lies in the artlessly simple performance of its star and the expressive use of fantastic signs and symbols to put forth its themes of change, duality and burgeoning eroticism. At the awakening of adult life there also lurks the spectre of death; people are not at all what they appear at the surface; within the family itself lurk bewildering demons of untold strength. Some of the imagery here is startlingly overt -- the pure white of Valerie's bedroom, the appearance of masked figures, the constant use of flame red fire, and her "father's" propensity for turning into a weasel as well as his iniquitous, smoldering lair. Viewers of a more political bent may want to read many of the signs shown here as related to ongoing historical events; for my part, I think the film plays much more simply as a modern fable. But Valerie and Her Week of Wonders seemingly has much more in common with the original tales of the brothers Grimm than the sanitized versions that came along after their death. In more ways than one, this is a fairy tale that has teeth. Though obviously a period piece in many ways, this gorgeously sumptuous example of post Soviet Czech film is an astonishing curio that succeeds by bringing a coming-of-age tale into the jet set age with a spectacular flourish of chromatic and sonic style. The sometimes puzzling and disjointed narrative is carried along by the ample tactile charm of its young star and the visual wizardry of its helmsman. Along with some of the other films included in the traveling Czech Horror and Fantasy Festival, Jires' film offers a unique glance at the sort of work that filmmakers in Prague sometimes turned to in the wake of Soviet tank treads. No longer able to operate freely as artists, those who stayed on to create cinema after 1968 often turned to the phantasmagoric as a simple way to avoid heavy handed political censorship. Though the results were not uniformly excellent (and the loss of some talent hurt the industry such that it has not yet returned to its mid '60s level), the example of Valerie and Her Week of Wonders demonstrates that such restrictions do not always bind so tightly that they cannot be transcended. That such artistry can't just be stamped out represents a great triumph of the human spirit, and when a film like this one resurfaces after three decades of absence it's a pleasure that shouldn't be foregone.

|

Thursday, January 08, 2026

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.