|

Passing OnBy Stephanie Star SmithDecember 30, 2003Each year at the Academy Awards, Hollywood takes a few moments to honor those who have joined the Choir Invisible during the previous year. Each year sees a number of people barely recognized by their industry peers, much less the viewing audience, along with a smaller percentage of renowned names (and the inevitable few "I didn't know he/she died"). This year, the Grim Reaper seemed to take a greater toll on Hollywood notables than in times past, with a number of influential and adored stars having shuffled off their mortals coils. We here at BOP would like to acknowledge the passing of these luminaries with a look back at the reasons why though they may be gone, they will certainly not be soon forgotten.Conrad L. Hall Reading Conrad L Hall's resumé is something like viewing a history of great cinema. The renowned cinematographer, who left this vale of tears on January 4th at the age of 76, was behind the camera on an amazing variety of seminal films of the 20th and 21st centuries. Beginning his career in 1958, Hall worked in both television and the movies; his TV credits include the atmospheric science-fiction series The Outer Limits.

Reading Conrad L Hall's resumé is something like viewing a history of great cinema. The renowned cinematographer, who left this vale of tears on January 4th at the age of 76, was behind the camera on an amazing variety of seminal films of the 20th and 21st centuries. Beginning his career in 1958, Hall worked in both television and the movies; his TV credits include the atmospheric science-fiction series The Outer Limits.

But it is his film career for which he is remembered, a career that spanned more than four decades and included such classics as Cool Hand Luke, In Cold Blood, Tell Them Willy Boy is Here, Electra Glide in Blue, Marathon Man and Day of the Locust. His more recent work included films as diverse as Black Widow, A Civil Action, Searching for Bobby Fischer, American Beauty and Road to Perdition. Hall even had a hand in an oddity known as Incubus, a bizarre and incomprehensible project shot entirely in the so-called universal language of Esperanto. As was sometimes the case with Hall's work, the beauty of the cinematography far outstripped the relative merits of the film itself, although the movie is not to be missed for connoisseurs of strange cinema. Hall received a total of ten Academy Award nominations for Best Cinematography, and won three Oscars. His first nomination was for 1965's Morituri; he was nominated again the following year for his work on The Professionals and a third time for 1967's In Cold Blood. But it was Hall's fourth nomination, for 1969's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, that brought the lens-man his first Oscar. Hall would be nominated four more times, for Day of the Locust, Tequila Sunrise, Searching for Bobby Fischer, and A Civil Action, before winning his second Oscar for Sam Mendes' American Beauty. Hall continued to work until the end of his days, receiving his tenth Oscar nod for his second collaboration with Mendes, Road to Perdition. Both the nomination and the resulting Oscar were received posthumously. Conrad L Hall used the camera as an artist uses a paintbrush, capturing and enhancing reality as displayed on the silver screen, finding beauty in the most unusual places and the oddest of sights. His keen eye and capable camera will be missed, but his legacy lives on in the celluloid he helped create.

Gregory Peck Gregory Peck. One can almost hear the actor's distinctive cadence when reading his name. The debonair California native, who joined the choir invisible on June 12th at the age of 87, was pre-med when bit by the acting bug. His tall good looks and suave manner were ideal for the leading man mold of 1940s Hollywood, and Peck achieved stardom almost from the beginning of his film career. In fact, Peck's second film, 1944's The Keys to the Kingdom, garnered the first of his five Academy Award nominations. Peck went on to star in such classics as Duel in the Sun, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Roman Holiday, Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, Guns of Navarone, Moby Dick, Cape Fear and How the West Was Won. Peck worked twice with Alfred Hitchcock, in Spellbound and The Paradine Case. He saw his second Oscar nod for 1946's The Yearling, and his third the following year for Gentleman's Agreement, directed by Elia Kazan. Peck also went to war for Hollywood, starring in such memorable pics as Twelve O'Clock High - which garnered Peck his fourth Oscar nomination - Pork Chop Hill and MacArthur. Peck also starred in one of Hollywood's first contemplations of the grim aftermath of nuclear war, On the Beach.

Gregory Peck. One can almost hear the actor's distinctive cadence when reading his name. The debonair California native, who joined the choir invisible on June 12th at the age of 87, was pre-med when bit by the acting bug. His tall good looks and suave manner were ideal for the leading man mold of 1940s Hollywood, and Peck achieved stardom almost from the beginning of his film career. In fact, Peck's second film, 1944's The Keys to the Kingdom, garnered the first of his five Academy Award nominations. Peck went on to star in such classics as Duel in the Sun, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Roman Holiday, Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, Guns of Navarone, Moby Dick, Cape Fear and How the West Was Won. Peck worked twice with Alfred Hitchcock, in Spellbound and The Paradine Case. He saw his second Oscar nod for 1946's The Yearling, and his third the following year for Gentleman's Agreement, directed by Elia Kazan. Peck also went to war for Hollywood, starring in such memorable pics as Twelve O'Clock High - which garnered Peck his fourth Oscar nomination - Pork Chop Hill and MacArthur. Peck also starred in one of Hollywood's first contemplations of the grim aftermath of nuclear war, On the Beach.

But most people remember Gregory Peck for his Academy Award-winning turn in 1962's To Kill a Mockingbird. As defense attorney Atticus Finch, Peck exuded integrity, navigating the complex waters of a racially-charged trial calmly and fairly. It was easy for moviegoers to understand Scout's hero-worship of her father; Finch, as embodied by Peck, was a man to be admired. Peck continued working well into his later years, with his roles covering such diverse fare as The Omen, The Boys from Brazil, Mackenna's Gold, Marooned, and Old Gringo. One of his last film roles was in Martin Scorsese's remake of Cape Fear; he had been the lawyer whose family is menaced in the original 1962 version. Whether playing a soldier or priest, lawyer or cowboy, Gregory Peck always conveyed a certain quiet dignity. He lent an air of elegance and refinement to any project that was graced with his presence, and no matter how outlandish the action surrounding him, Peck remained the quintessential gentleman.

Hume Cronyn Hume Cronyn was one of those rare actors who achieved greater fame as he came closer to the end of his life. When he left this plane of existence on June 15th, the 91-year-old actor was best known for the films he did after the age where most folks retire, gaining his greatest fame for his turn in Ron Howard's Cocoon. Roles in *batteries not included and the Cocoon sequel followed, along with a number of acclaimed television adaptations of stage plays.

Hume Cronyn was one of those rare actors who achieved greater fame as he came closer to the end of his life. When he left this plane of existence on June 15th, the 91-year-old actor was best known for the films he did after the age where most folks retire, gaining his greatest fame for his turn in Ron Howard's Cocoon. Roles in *batteries not included and the Cocoon sequel followed, along with a number of acclaimed television adaptations of stage plays.

In fact, Cronyn was better known for his stage work in his early years than for the work he did in films. Although he appeared in such classics as Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat and The Postman Always Rings Twice, he generally played one of many supporting roles; much of his early career was as a "Hey, it's that guy!" actor. With the advent of television, Cronyn expanded his stage work to the small screen, appearing in adaptations of A Doll's House, Juno and the Paycock, and The Moon and Sixpence, and in later years Foxfire, To Dance with the White Dog, and Broadway Bound. Cronyn received a number of Emmy nominations and awards, and was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his work in The Seventh Cross. But it is his appearances opposite his wife of 52 years, Jessica Tandy, for which audiences remember Cronyn. Though the material may have been less weighty than some of his stage roles, it was these later roles that provided audiences with a charming reminder that being over 60 - or even older - doesn't mean life, or love, comes to a screeching halt.

Katharine Hepburn Katharine Hepburn was nearly as famous for her off-screen life as she was for her on-screen roles. Strong-willed and stubborn, with a quick mind and sharp tongue, Katharine Hepburn was a force to be reckoned with, and woe be unto the studio exec or director who took her lightly. In an era when women were supposed to be submissive and meek, Kate said what she thought and went after what she wanted; considered difficult to work with from the very beginning of her career, she was also undeniably talented, a fact which kept her working in Hollywood when a lesser actor would have long since been shown the door.

Katharine Hepburn was nearly as famous for her off-screen life as she was for her on-screen roles. Strong-willed and stubborn, with a quick mind and sharp tongue, Katharine Hepburn was a force to be reckoned with, and woe be unto the studio exec or director who took her lightly. In an era when women were supposed to be submissive and meek, Kate said what she thought and went after what she wanted; considered difficult to work with from the very beginning of her career, she was also undeniably talented, a fact which kept her working in Hollywood when a lesser actor would have long since been shown the door.

Katharine Hepburn is largely cemented in the public mind to her longtime love, Spencer Tracy. The pair did nine films together, and their on-screen relationship crackled with a passion and intelligence that to this day is held as a standard for cinematic pairings. But Hepburn worked with other greats in other iconic American films. She starred opposite Cary Grant in four films, including the prototypical screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby and the witty Philadelphia Story, a film which served as a comeback of sorts for Hepburn and which earned her one of 12 Academy Award nominations. In fact, only Meryl Streep has received more Oscar nods than Katharine Hepburn, and no actor matches her record of four wins, three of which came after the age at which Hollywood seems to ignore women these days. Amongst the classis movies that Hepburn enlivened with her presence are Holiday, Adam's Rib, Woman of the Year, Rooster Cogburn, Little Women, The Madwoman of Chaillot, and Pat and Mike. Hepburn received Oscar nods for Long Day's Journey into Night, Suddenly, Last Summer, The Rainmaker, Summertime, African Queen, Woman of the Year, Philadelphia Story and Alice Adams, and won for On Golden Pond, The Lion in Winter, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner and Morning Glory. In later years, Katharine Hepburn did a number of TV movies and wrote a number of books, including an autobiography and a chronicle of the making of The African Queen. But the moviegoing public will always remember her with Spencer Tracy, his equal in every way, giving as good as she got, and loving every minute of it. Her great gift was in making us love it, too.

John Schlesinger John Schlesinger actually started out as an actor. The celebrated director, who worked on stage and in radio and television in addition to the movies, supplemented his early acting work directing documentaries for the BBC. After his first feature film - a documentary on London's Waterloo Station called Terminus - won a British Academy Award, Schlesinger left acting for good to concentrate on directing.

John Schlesinger actually started out as an actor. The celebrated director, who worked on stage and in radio and television in addition to the movies, supplemented his early acting work directing documentaries for the BBC. After his first feature film - a documentary on London's Waterloo Station called Terminus - won a British Academy Award, Schlesinger left acting for good to concentrate on directing.

His films include some of the most stylish, entertaining and informative projects of the last half of the 20th century. He received his first Academy Award nomination for Darling, a satire of the mod London scene which made Julie Christie a star. His other films include Marathon Man, Day of the Locust, Falcon and the Snowman and The Believers. Schlesinger received two more Oscar nods, for 1971's relationship drama Sunday, Bloody Sunday, and for the only X-rated film to win a Best Picture Oscar, 1969's Midnight Cowboy, the film for which Schlesinger won his Academy Award. John Schlesinger's film output slowed as the last century came to a close, as failing health caught up with the legendary helmer, and a stroke in 2000 left him debilitated and unable to continue in the career he loved. But his work had already left its mark on cinema, a proud legacy that sets the standard for generations to come.

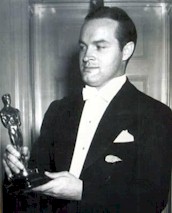

Bob Hope Leslie Townes Hope achieved many milestones in his lifetime: reaching the century mark, being hailed as a national treasure, employing the new medium of television to increase his exposure and enhance his legend. But one of his oft-expressed goals eluded him; although Bob Hope received an unprecedented four honorary Oscars, in addition to receiving a lifetime membership in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian award, he never won the Oscar that he so often publicly coveted.

Leslie Townes Hope achieved many milestones in his lifetime: reaching the century mark, being hailed as a national treasure, employing the new medium of television to increase his exposure and enhance his legend. But one of his oft-expressed goals eluded him; although Bob Hope received an unprecedented four honorary Oscars, in addition to receiving a lifetime membership in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian award, he never won the Oscar that he so often publicly coveted.

Not that missing out on earning that elusive golden statuette in any way diminished his career. The tireless entertainer of the military in far-off places saw a great many streets, schools, hospitals and airports in and around Burbank named after him. He received honors galore, including a knighthood, a Kennedy Center Honor, a National Medal of the Arts, a Congressional designation as an honorary veteran, and enough honorary degrees to wallpaper your average three-bedroom house. He holds two Guinness World Records, one for the most awards, and one for the most years under contract to the same network. He was feted and celebrated as each milestone birthday arrived, and continued doing TV specials for NBC and entertaining the troops well into his eighth decade. Hope was an American icon. But what is sometimes overlooked is that he was also a pretty decent film comedian, with a number of which are considered film classics. His big break came in The Big Broadcast of 1938, a sort of on-screen variety show with a minimal plot that served as an excuse to showcase a bunch of stars and lesser-knowns. It was in this film that Hope first sang what became his signature tune, "Thanks for the Memories"; over the years, simply playing the first few bars of the song signaled an appearance by the ski-nosed comic. He cemented his fame when he began appearing alongside Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour in the Road pictures. In between, Hope starred in a number of comedies playing variation of the same character: slightly craven, decidedly greedy, with an eye for the ladies and a knack for getting himself into deep trouble. This persona worked for a string of films spanning more than two decades, and included such classics as The Cat and the Canary, The Ghost Breakers, My Favorite Blonde, The Paleface, Monsieur Beaucaire, and Fancy Pants. Hope even made a foray into more serious fare, starring as legendary New York mayor Jimmy Walker in Beau James, a role that showed a depth and characterization one acquainted only with Hope's more renowned work would hardly expect. As the 1960s wore on, however, Hope's brand of humor fell out of public favor; by the early '70s, tepid reviews and even more lukewarm box office led Hope to abandon films for the safe haven of television. One of the first stars to embrace the new medium, Hope reigned supreme with his quarterly NBC specials. Hope remained under contract to NBC until the late '90s, when the network chose not to renew the long-standing contract. By that time, however, Hope's TV appearances had become infrequent; frail with age and in failing health, Hope mostly retired from public view. His comedy star, which once shown brightly, had become tarnished by the continued appearances of performer who didn't quite know when to leave the stage. When Hope finally shuffled off to that great stage in the sky, he was mourned as a national hero. Flags were placed at half-staff, and memorials galore appeared on TV and in newspapers. But with the loss also came an opportunity to rediscover the Bob Hope that first burst onto the public scene in 1938; self-deprecating, never afraid to sacrifice his dignity in pursuit of a laugh, a truly funny man who could make even a cowardly skirt-chaser endearing. That Hope, fortunately, survives on celluloid to delight future generations with his unique charm.

Charles Bronson Charles Bronson, born - and sometimes credited as - Charles Buchinsky, spent most of his career as a journeyman character actor. Generally cast as one of the soldiers in the platoon, the cowboys in the posse, or the criminals in the gang, Bronson has an active film career that included a number of classic films, including House of Wax, The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and The Dirty Dozen. But it was the 1974 bloody revenge-fantasy Death Wish that sealed Bronson's tough-guy image in the public mind, and made him a somewhat-unlikely leading man at the age when most leading men are turning to character roles. Tapping into a little-recognized vein of anxiety and middle-class dread over what was seen at the time as a violent urban society out of control, the Death Wish franchise gave moviegoers the vicarious thrill of seeing those who appeared to have taken advantage of a criminal justice system some deemed too concerned with the rights of the perpetrator get their just desserts. The Death Wish films made Bronson a star, and he continued making films of that genre for the remainder of his career.

Charles Bronson, born - and sometimes credited as - Charles Buchinsky, spent most of his career as a journeyman character actor. Generally cast as one of the soldiers in the platoon, the cowboys in the posse, or the criminals in the gang, Bronson has an active film career that included a number of classic films, including House of Wax, The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and The Dirty Dozen. But it was the 1974 bloody revenge-fantasy Death Wish that sealed Bronson's tough-guy image in the public mind, and made him a somewhat-unlikely leading man at the age when most leading men are turning to character roles. Tapping into a little-recognized vein of anxiety and middle-class dread over what was seen at the time as a violent urban society out of control, the Death Wish franchise gave moviegoers the vicarious thrill of seeing those who appeared to have taken advantage of a criminal justice system some deemed too concerned with the rights of the perpetrator get their just desserts. The Death Wish films made Bronson a star, and he continued making films of that genre for the remainder of his career.

But Bronson is also remembered for another, equally unlikely, role: that of loving husband and caregiver. The gruff actor displayed immense compassion and devotion during the illness of his beloved wife, Jill Ireland. It is the two sides of his persona, tough man of action and devoted family man, that will continue to draw audiences to his films.

Elia Kazan Elia Kazan is an interesting study in how actions taken outside Hollywood and its environs can affect one's standing in the Hollywood community.

Elia Kazan is an interesting study in how actions taken outside Hollywood and its environs can affect one's standing in the Hollywood community.

Born Elia Kazanjoglous, the immigrant Kazan was one of the first directors to champion The Method for cinematic acting. His early resumé reads like a list of cultural benchmarks, and includes such films as On the Waterfront, A Streetcar Named Desire, Gentleman's Agreement, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and East of Eden. Kazan worked with some of the most legendary actors of the day, including Gregory Peck, Marlon Brando, and James Dean. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director for A Streetcar Named Desire and East of Eden, and won Oscars for On the Waterfront and Gentleman's Agreement. Then came Senator Joe McCarthy. In the early 1950s, the Cold War was just beginning, and Americans were becoming increasingly fearful of Communism in general and the USSR in particular. McCarthy was a junior senator with an undistinguished career who, sensing an opportunity for self-aggrandizement, began an unrelenting campaign to uncover so-called Communist infiltrators who had wormed their way into the very fabric of American society and intended to destroy the country from within. After whipping up a frenzy in Washington, Tailgunner Joe created the House Un-American Activities Committee, ostensibly to discover these Communist spies and prevent them from carrying out their evil plan. In reality, the HUAC, as it became known, was little more than an avenue for Joe McCarthy to promote Joe McCarthy. But for two years, McCarthy held sway over a series of hearings during which American citizens were mercilessly grilled concerning their political affiliations. To answer the infamous question, "Are you now or have you ever been..." in the affirmative was career suicide; to refuse to answer the question was also career suicide. And in Hollywood, where being a Communist was once as much a fad as Botox is now, there was almost no way to win. Unless you became what Tailgunner Joe and his witch-hunters called a "friendly witness". The one sure way to save yourself from being blacklisted, especially if you had actually once been a Communist, was to name names of people you "knew" to be Communists. Now whether you actually had any proof that any of the people named were now or ever had been was beside the point; giving McCarthy names allowed him to continue his campaign and increase his power. As long as he could convince the American public that there were Communist agents in their very midst, looking to subvert the unsuspecting populace through seemingly innocent forms of entertainment, McCarthy remained the center of attention and his power remained unchecked. And Elia Kazan named names. Kazan destroyed careers whilst preserving his own, and in many quarters of Hollywood, he became as blacklisted as the writers and directors he helped McCarthy banish. Kazan continued to make films, and ironically had some of his greatest successes, including one of his Oscars, after his appearance before Tailgunner Joe, but as the '60s dawned, Kazan's output slowed, and his career never entirely escaped the taint of what many perceived as a cowardly act designed to save his own skin by sacrificing others. Kazan's testimony before HUAC continued to stir controversy throughout his life, most notably when AMPAS decided to award the director an honorary Oscar at the 1999 ceremony. The decision created a furor in Hollywood, with a number of stories being done about the appropriateness of honoring someone who had so spectacularly - and by his own admission, without remorse - turned on his fellow members of the film community. Although the award presentation occurred without incident, many prominent members of the current Hollywood community left the auditorium just as the honor was announced, and many of those who remained in the audience refused to applaud or otherwise acknowledge Kazan. Nearly half-a-century later, his death on September 28th at the age of 93 generated as many stories about his actions during the McCarthy hearings as it did discussions of his films.

Donald O'Connor Donald O'Connor was that rare celebrity whose fame rested mostly on one film.

Donald O'Connor was that rare celebrity whose fame rested mostly on one film.

Oh, but what a film that was. O'Connor, who danced into the afterlife on September 27th at the age of 78, starred in a number of MGM musicals, the vast majority of which you wouldn't recognize if you heard the titles. He also starred alongside a talking mule named Francis in a series of films that are mostly forgotten now. But the film for which you and I and most of the rest of the Western world know him is the seminal Singing in the Rain, where he lit up the screen alongside Debbie Reynolds and Gene Kelly as one of a company of actors dealing with the transition from silent films to talkies. The clip played on the local TV news during reports of his demise is of his signature number in the film, a slapstick tour-de-force called "Make 'Em Laugh". The dizzying acrobatics and pratfalls, the immense skill of a physical comedian projected in dance, is a memorable moment not only of that film, but of highlight films of great dance and comedy moments throughout the ages. O'Connor appeared in other films after Singing in the Rain, including a couple of the aforementioned Francis the Talking Mule vehicles. He also ventured into television in the early years, starring in an eponymous variety show with a thin plotline that was basically an excuse for O'Connor to sing and dance each week. But mostly, Donald O'Connor is remembered for the breezy, tuneful bit of classic Hollywood froth known as Singing in the Rain, and the amazing, show-stopping number extolling the virtues of being the clown. Certainly in O'Connor's case, the song's premise turned out to be true.

|

Tuesday, December 30, 2025

© 2006 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.