|

|

Sole Criterion: A Hollis Frampton OdysseyBy Brett Ballard-BeachJuly 5, 2012

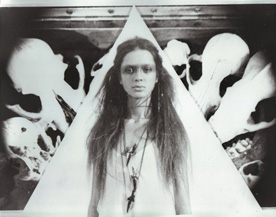

I have had the opportunity to see the three longest pieces included in the Criterion package on film at various points over the last decade: Zorn’s Lemma, Winter Solstice, and (nostalgia). The first and last were screened as part of classes I took at NYU, and the middle one was shown by a local Portland collective known as Cinema Project that holds twice yearly programs of avant-garde cinema each featuring about a dozen screenings. (nostalgia) made such an impression on me at the time, and continues to, that I would be accurate in assessing it as my favorite short film of all time. It, alongside “The Body” episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer - see my November 11, 2009 Chapter Two column “Buffy, Baby, and Brett for more on that - has given me more to ponder about the nature and meaning of memory and loss than any other piece(s) of filmmaking that I have encountered. The elements of (nostalgia) are bracing in their simplicity: A narrator recounts the histories behind 12 photographs taken by Frampton, most from at least ten years prior. As the narrator speaks, each photograph is seen resting on what the audience soon discovers is a hot plate. As each (approximately) three-minute anecdote is related, the photograph smokes, smolders, and soon is consumed by the heat. If the photo burns quicker or the story is shorter, than there is silence on the soundtrack, as the husk of the photo crumbles and ash takes to the air. The first catch is that in each case, the narrator is not describing the photo we are then looking at, but the one that is next to appear. Thus, the film begins with a photo that has no story and ends with a rather breathless, purposely cliffhanger-ish encapsulation of a photo that we will not see. In the other instances, we must keep the narration from before fresh in our mind to see how the photograph compares to the image we have created. This comparison must then be done in the “shadow” of paying attention to the current description. It’s like a slightly more cerebral cinematic take on the childhood game Concentration.

|

|

|

|

|

Friday, November 1, 2024

© 2024 Box Office Prophets, a division of One Of Us, Inc.