Sole Criterion: A Hollis Frampton Odyssey

By Brett Ballard-Beach

July 5, 2012

The second catch is that, though the narration is all first person about Frampton’s life and experiences, he isn’t the one talking (save for a few utterances during the first few seconds). Fellow avant-garde filmmaker and friend Michael Snow handles the speaking duties and his Canadian accent and more overt embrace of the humor in Frampton’s text shift the vibe from Frampton’s erudite professor to more of a Garrison Keillor of the Great White North. Frampton’s words are often critical in their self-analysis and the 36-minute film could be seen, on a most basic level, as an act of anti-creation, of placing one’s artistic endeavors on the funeral pyre. (It should be noted again, though, that these are still photographs burning, not negatives, leaving open the possibility that they could be “recreated”.)

In the simple disjunction between word and image (which he takes to its most extreme limits when he charts a relationship breakup in his work Critical Mass), Frampton suggests the way in which the “fact” of the past can become entangled by and wrestle with our memory of the event, or become rewritten through changes in ourselves over time, or by the act of forgetting what once seemed so important to document for posterity. Frampton was 35 when he filmed (nostalgia) and looking back on photos he had taken from his early to mid-20s. Whether it’s from Snow’s intonation or Frampton’s embrace of the parenthetically qualified emotion of the title, the film resists the condescending examination of someone older looking back on his youth with superiority or some “there but for the grace of God go we all” ennui. There is an element of melancholy and more than a dash of wry humor, but the stories and the project itself are marked by the skill of taking an honest account of a handful of moments in a life, and stepping outside of that history in order to do so.

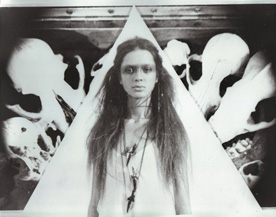

All of this is enhanced by the centering of each photograph on the hot plate and in the frame, permitting the cloud of smoke to arise as if out of nowhere before the spiral of the hot plate element becomes seared into the picture, and often allowing someone’s face to be perfectly aligned so that it remains as the final portion of the photograph to become blackened (note this particularly in regards to Frampton’s self-portrait.)

Throughout the films that make up this Odyssey, Frampton shows a remarkable feel for capturing the physicality of someone’s features in a matter of seconds. This is noticeable from the outset in 1966’s Manual of Arms, a b&w silent film featuring appearances by the close-knit group of Manhattan artists with whom he was friends at the time, each represented in quick succession and later in a more “extended” offhand manner (the film runs 17 minutes). The pair of drama students who became his first actual actors - in 1971’s Critical Mass - play at a Cassavetes-like improvised domestic squabble, and Frampton structures their flamboyant gestures, profane epithets, and defiant tones by allowing the audio to lose sync with the image, or repeat the recorded sound in triplicate, like a scratched record echoing in a cave. The man and woman are no longer on the same wavelength, and neither are their words.

Magellan was meant to be a 36-hour collection of 1000 films, to be viewed over the course of a full year and then some (ever a master of structure and form, Frampton created his own calendar for this project, and had most days plotted with their programming, even if the films were more conceptualized than realized at that point). A six-minute excerpt from one of these pieces features a wholly unsettling employment of canned audience applause on the soundtrack. Thinking about it even now makes me queasy. I can only describe the sound as the falsely jovial hand claps of the eternally damned, as if Frampton had drained the warmth out of a simple human gesture. Furthermore, the manner in which Frampton deploys this on the soundtrack, delaying it or even withholding it, but always returning to it produces a dread anticipation of Pavlovian proportions.

Continued:

1

2

3

4

|

|

|

|