In Passing, 2006

Part II

By Stephanie Star Smith

January 16, 2007

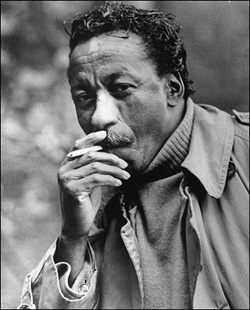

Gordon Parks

Gordon Parks

Gordon Parks was a pioneer in many areas. He was one of the first African-American photographers for a major publication as well as being first African-American to direct a motion picture for a major studio.

The youngest of 15 children, Parks' mother taught him that being black was no excuse for failing; as he would tell in later years, his mother told him he could do anything a white boy could do, "...and do it better, or don't come home." It was this instruction and support that would lead him to break the racial barriers of the time and succeed in the photographic arts. His mother died when he was a teenager, and he was sent to live with a married sister; he and his brother-in-law didn't get along, however, and he was soon put out on the street. He lived hand-to-mouth, sleeping in trolley cars, and took a number of odd jobs to get by, including a piano player in a bordello, a factotum at an all-white country club, and a waiter on a luxury train. Struck by photographs of migrant workers he saw in a magazine, Parks decided he wanted to try his hand at photography; working with a cheap camera bought at a pawn shop, his first roll of film so impressed the clerks developing it that they encouraged him to get a job doing fashion shoots. His first assignment was very nearly a disaster, though, as he overexposed all but one frame. This one frame, however, was good enough to catch the eye of Joe Louis' wife, Marva, and she convinced parks to move to Chicago, where he built up a business doing portraits of society women.

Over the next several years, Parks drifted from city to city, building up his portfolio and developing his eye for images. An exhibition of his photos documenting life on the South Side of Chicago secured a job at the Farm Security Administration, where he began to document the everyday discrimination faced by the African-American people working in a white society. He also continued to work in fashion photography, landing many spreads in Vogue magazine. A series of photos on the life of a Harlem gang member was his entrée into working for Life, and he spent the next several years photographing everything from fashion to sports to poverty and racial segregation; he also did portraits of celebrities and activists such as Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali, and Barbra Streisand. One of his photo essays, a poor Brazilian boy dying from bronchial pneumonia, encouraged the public to send donations to the child and his family which ultimately saved the boy's life.

During the ‘50s, Parks moved to Hollywood, where he became a consultant to many movie productions and did a number of documentaries for National education Television on life in the ghetto. His eye for images and framing eventually led to an offer from Warner Bros to direct a feature film version of his autobiography, The Learning Tree, making him the first African-American to direct a film for a major studio. But it was his second feature, the seminal Shaft, that made his name in Hollywood; the film is credited, along with Sweet Sweetback's Baad Asssss Song, with starting the blaxploitation genre (although Parks didn't consider his films to be blaxploitation pictures). He followed that success with the sequel, Shaft's Big Score, which took in less at the box office than its predecessor, but was still considered a success. The film also gave him the chance to showcase his musical abilities; he wrote the score for the film. He was also an accomplished jazz pianist and composer, creating several works in his lifetime, including a ballet honoring Martin Luther King, Jr, which he also choreographed. An accomplished jazz pianist, it was only natural that Parks would direct a biopic of legendary bluesman Huddie Ledbetter, one of only eight films Parks directed in his lifetime.

In addition to his directing and photography careers, Parks was an avid civil rights campaigner, a painter - he exhibited his photo-related artwork in several galleries - and a founder of Essence magazine. When he joined the Choir Invisible on March 7th after a bout with cancer, he left behind a legacy of pioneering work that helped illuminate the plight of the downtrodden and minorities in the US.

|

|

|

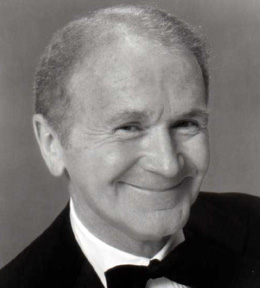

Maureen Stapleton

Maureen Stapleton

Maureen Stapleton used to joke that she was born old, a reference to the number of matronly roles she was cast in almost from the time she began acting. But the woman born Lois Maureen Stapleton - not, as popular myth would have it, related to All in the Family's Jean Stapleton - had a lively wit and a self-deprecating humor that served her well for the earth mother-type roles she often played on stage and screen.

Stapleton expressed few illusions about her looks or her talent, and often credited her passion for acting to her desire to escape some of the vicissitudes of growing up with a less-than-perfect face and body. Not that Maureen Stapleton was ugly by any means, but she was the first to admit that she wasn't a classical beauty, and felt her acting ability was what would carry her on to success.

She was, of course, right.

Stapleton began to get stage work almost from the time she arrived in New York at age 17, and quickly rose through the ranks. She originated the role of Serafina in Tennessee Williams' The Rose Tattoo, for which she won a Tony for Best Supporting Actress. She also performed in many television productions in what is often referred to as The Golden Age of TV Drama, racking up appearances on such stalwarts of the era as the Philco Television Playhouse, the Alcoa Hour, Studio One, Kraft Television Theatre and Playhouse 90; and early television series such as Car 54, Where Are You? and Naked City. She didn't ignore the silver screen during this time, either, taking roles in A View From the Bridge and The Fugitive Kind, a reworking of the Tennessee Williams play Orpheus Descending. And of course there was still her stage work, including Toys in the Attic and Orpheus Descending; ironically, although she played the lead character of Lady Torrance on Broadway, she was relegated to a supporting role in the film. She won another Tony, this time for Best Actress, for the 1971 play The Gingerbread Lady; she was nominated for four additional Tonys, for her work in The Cold Wind and the Warm, the aforementioned Toys in the Attic, Plaza Suite and The Little Foxes. Stapleton holds the distinction of being one of ten actors to win the equivalent of the Triple Crown in acting: her Tony for The Rose Tattoo, an Emmy for Among the Paths of Eden, and an Oscar for Reds. And as if that wasn't impressive enough, she won a Grammy for Best Spoken Word Recording for her 1975 rendition of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Stapleton kept busy in films, TV and on the stage for most of her life, with her last role coming in 2003's Living and Dining. Her gregarious nature also made her a staple of the talk show circuit; she was a frequent guest on The Tonight Show when Johnny Carson was host, where her self-deprecating, often ribald wit was afforded a perfect showcase. That wit was on full display when, appearing in the press room after winning her Oscar, she was asked how it felt to be recognized as on of the greatest actresses in the world. Her reply? "Not nearly as exciting as it would be if I were acknowledged as one of the greatest lays in the world." When commenting on the frequent question posed to all successful actors, she stated, "I've been asked repeatedly what the 'key' to acting is, and as far as I'm concerned, the main thing is to keep the audience awake." Her assessment of her own physical appearance was no less down-to-earth; when asked if she worried about losing her beauty, she said she never had that problem, going on to add, "People looked at me on stage and said, 'Jesus, that broad better be able to act'." That she could.

Her honesty extended to her foibles as well. She admitted that her father had been an alcoholic, and that she herself had a long-standing drinking problem, although she never was so unprofessional as to drink whilst performing. It was an ill-kept secret on Broadway, however, that a bottle of vodka was a permanent fixture in her dressing room, and she headed straight for it when she got off-stage. She also had an aversion to flying and elevators; she traveled by train across the country or by ocean liner to location shoots.

In addition to her performing awards, she was also honored for her contributions to the theatre. She received the Actors Studio Award in 1980, and was being inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame in the following year. The year 1981 also saw the Hudson Valley Community College in her hometown of Troy, New York renamed its theatre in her honor, and in 1985, she became one of that select corps upon whom a Kennedy Center Honor is bestowed. She displayed her customary self-deprecating wit concerning all her awards and honors, saying at one point that when the curtain went up or the cameras rolled, she "did the best [she] could; and that she loved the challenge and the opportunity to leave reality behind and become someone else." During her Academy Award acceptance speech, she tanked a few individuals by name, and then ended by saying, "I would like to thank everyone I've ever met".

When chronic pulmonary disease brought Maureen Stapleton to the River Styx on March 13th, the world lost not only a broad that was more than able to act, but a lady with an earthy wit and an unassuming air who was a great friend to all forms of the dramatic arts.

|

|

|

June Allyson

June Allyson

To the Baby Boom generation, June Allyson is the lady who did the Depends commercials, but to what has become known as the Greatest Generation, June Allyson was a song-and-dance girl who brightened a string of hit musicals for MGM with her charming smile and engaging personality.

Born Eleanor Geisman in the Bronx, Allyson didn't seem destined to be a dancer. Injured in an accident when she was eight years old, she spent four years in a steel brace. Swimming therapy helped restore her mobility, and an affinity for Astaire/Rogers movies instilled in her a desire for dancing lessons. In high school, she entered a number of dance contests, and was eventually featured in several musical shorts. Soon the bright lights of Broadway beckoned, and Allyson made her debut in the 1938 musical Sing Out the News. She worked her way up through the chorus, eventually understudying Betty Hutton in Panama Hattie. When Hutton came down with the measles, Allyson had her chance, and the old cliche about going out a member of the chorus but coming back a star came true; she so impressed director George Abbott with her performance that he cast her as the lead in his next musical, Best Foot Forward. When she reprised her role for the screen version, MGM immediately signed her to contract, and she spent the next dozen years thriving under the studio system. It was during this time that she met her first husband, Dick Powell; the two were married in 1945, and despite a stormy relationship and infidelities on both sides, remained married until Powell's death in 1963.

Although she worked steadily for MGM throughout the '40s and '50s, she largely retired from film work upon Powell's death, although she continued to appear both on and off-Broadway and do guest appearances on television series. This was also the era during which those infamous Depends commercials began, which were born of her advocacy for those suffering with incontinence. By giving a condition that many adults found embarrassing to discuss, even with their doctors, a familiar and famous face, Allyson is credited with helping lessen the stigma associated with the malady, and the June Allyson Foundation is still active in advancing the cause through public education and medical research. She also became active in preserving the history of MGM, and in fundraising for both the Jimmy Stewart and Judy Garland museums. Allyson herself proved a valuable resource for those looking to compile and safeguard the history of MGM and the major Hollywood studios of old.

As the 20th century drew to a close, Allyson took on fewer and fewer acting jobs, and had largely retired from show business altogether when the final curtain was rung down on July 8th, but her singular voice and wholesome image endures in the films she made for the studio she loved, which she called her "mother and father, mentor and guide, [her] all-powerful and benevolent crutch", and whose legacy she sought to protect and conserve for future generations.

|

|

|

Red Buttons

Red Buttons

Sometimes you learn so much more about a celebrity when you read his or her obituary than you ever knew from watching him/her on-screen.

Take Red Buttons, for instance. The man born Aaron Chwatt started out as a stand-up comic and singer, with aspirations of becoming a songwriter as well as a comedian. Acting, for Red Buttons, came about almost by accident.

Buttons started his show business career when he was a kid, singing on street corners for whatever spare change passersby would give. He soon graduated to working as a singing waiter at Dinty Moore's Tavern in the Bronx, which is where he acquired his stage name; the uniform the red-haired young man wore had 48 buttons, and patrons paired the usual sobriquet for flame-hued tresses with the prodigious number of buttons and the rest, as they say, is history. At 16, he paired up with fellow future thespian Robert Alda for comedy act that worked the Catskills, the most prestigious venue on what was called the Borscht Belt and the height of success for comedians of that era. After working steadily on the burlesque circuit for several years, Buttons was cast in his first acting role, the Broadway play Vicki. World War II intervened not long thereafter, however, and Buttons served his country in the Marine Corps, although this hardly put a crimp in his show business career; he was cast in Moss Hart's service-themed play Winged Victory. The play also served as his entree into Hollywood when he reprised his role in the film version.

Once Buttons completed his wartime service, his show business career went into high gear; he did Broadway plays and worked as the stand-up with big band orchestras. His success grew to the point where the nascent medium of television soon took notice, and Buttons was given his own show, appropriately titled The Red Buttons Show, which. The variety series ran for three years and garnered Buttons an Emmy as Best Comedian. After his series finished its run, he took roles in other TV shows, and in 1957, he got his biggest break on the silver screen in Sayonara, co-starring Marlon Brando. Buttons' portrayal of an American soldier encountering prejudice because of his love for a Japanese woman garnered him an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor.

Buttons worked steadily in both film and television for the remainder of his life, garnering award nominations and critical and popular acclaim along the way. He received Golden Globe nominations for his work in the films Harlow and They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, showcased his comic timing and singing ability on the Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts, appeared on game shows and talk shows, did charity events and telethons, and even performed in Las Vegas for a number of years. Buttons even eventually realized his ambition to become a songwriter, joining ASCAP in 1963 and writing and recording a number of popular songs.

Advancing age seemed to slow Red Buttons down but little; he continued to work nearly up until his July 13th appointment with the Ferryman. It has been said that loss of life is to be mourned, but only if that life was wasted; by that standard, Red Buttons should not be mourned, but celebrated for having spent his time in this vale of tears as wisely and as well as could any man.

|

|

|

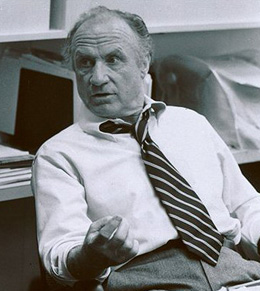

Jack Warden

Jack Warden

In Hollywood, it really pays to be a character actor. Oh, maybe not in terms of the big-money per-picture payday, but when it comes to working steadily over the long term, being a character actor is where it's at.

Jack Warden is a case in point. Born John H Lebzelter - German for honey-cake baker - the son of a Jewish father and Irish mother started out as a fighter. Literally. Expelled from his high school in Louisville, Kentucky for constantly fighting, Warden took the ring professionally, boxing as a welterweight under the name Johnny Costello; he took his mother's maiden name as his ring name at his mother's urging. Fearing the anti-Semitism of the time, Warden's mother encouraged her son to hid his ethnic identity; in his later years, however, he became quite proud of his heritage and enthusiastically embraced both his parents' cultures.

Warden's professional boxing career turned out to be a brief one, as the purses weren't enough to pay the bills, so he quit boxing and took work as a bouncer in a nightclub and as a lifeguard before joining the US Navy in the years leading up to the start of World War II. After his three-year hitch was finished, Warden moved on to the Merchant Marines, as that was a better-paying gig than the Navy. He started as a water tender in the engine room, but being stuck in the bowels of the ship on convoy runs, with Axis aircraft trying to sink the ship didn't turn out to be much more appealing; in later years, Warden said that his Merchant Marine service ended his "romance with the life of a sailor". He left the Merchant Marine in the middle of World War II, and still wanting to serve his country, Warden enlisted in the Army, becoming a paratrooper with the elite 101st Airborne Division, which served as the first offensive wave for the invasion of Normandy. Warden, however, was not involved in that historic battle; he had broken his leg very badly in a nighttime practice jump in advance of the invasion and was in a VA hospital recuperating when the Allies stormed Omaha Beach. But by missing the battles on D-Day, Jack Warden gained a new career direction; a fellow patient, an actor in civilian life, gave Warden some reading material to pass the time: a play by Clifford Odets. Warden was so enraptured by the play the he decided he would become an actor when he was discharged.

After rejoining his unit in time to see action at the Battle of the Bulge, Warden returned to civilian life and promptly embarked on his new career. He used his GI Bill benefits to study acting in New York, and also joined the Dallas Theatre Company, taking his father's middle name and pairing it with the common nickname for his given name to create his stage name. Steady work came his way quite quickly, and he spent five years shuttling between Texas and New York to meet the demand for his talent, a demand which only grew greater with the advent of television. After several years as a journeyman actor in regional productions and bit parts on TV, he made his Broadway debut in a revival of Clifford Odets' Golden Boy, bringing him full circle to the genesis of his desire to act. Shortly thereafter, Warden joined two fellow World War II vets, Lee Marvin and Charles Bronson - then billed under his birth name of Charles Buchinsky - in the cast of You're in the Navy Now; it was the feature film debut for all three (although Marvin and Warden were uncredited). More film work soon followed, including a sympathetic barracks mate to Montgomery Clift and Frank Sinatra in From Here to Eternity; Warden's breakout role as Juror Number Seven in 12 Angry Men; and the submarine drama Run Silent, Run Deep. Warden was also in demand on television, appearing in such classic shows as Inner Sanctum, Mr Peepers, Kraft Mystery Theatre, and in the premiere episode of the Twilight Zone. The episode, titled The Lonely, proved to be Warden's breakout TV role, affording him the chance to show a vulnerability and sensitivity that had not been on display in his previous film roles.

The '60s and '70s were prime decades in Jack Warden's film and television careers. It was during this 20-year span that Warden gave an Emmy-winning performance as Coach Halas in Brian's Song; was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for Shampoo and Heaven Can Wait; portrayed Harry M Rosenfeld, the Washington Post's Metro News editor in All the President's Men, and Lieutenant-General Mordechai Gur in Raid on Entebbe; assayed the roles of the President of the United States in Being There and the corner man in to Jon Voight's aging pugilist in The Champ; appeared as the gun-toting judge in...And Justice for All and the German doctor in Death on the Nile; and as if that wasn't enough, was the lead character in not one but two TV series: Jigsaw John and The Bad News Bears (neither of which lasted long). All this, of course, was in addition to many guest-starring roles on a variety of TV series and parts large and small in films that were the same.

The final two decades of the 20th century were a mixed bag for Jack Warden's acting career. While the number and variety of roles in both television and feature films remained much the same, the quality of the material was less so, although there were still highlights, amongst them The Verdict and Bullets Over Broadway. Warden also made one final stab at a long-running television series, portraying the eponymous detective in Crazy Like a Fox; alas, the gods of television decreed it was not to be. The 2000 film The Replacements was Jack Warden's final role before he joined the Choir Invisible on July 19th. Heaven could wait after all, and the pantheon of great characters on the silver screen and the small is all the better for that.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|