In Passing, 2006

Part III

By Stephanie Star Smith

January 23, 2007

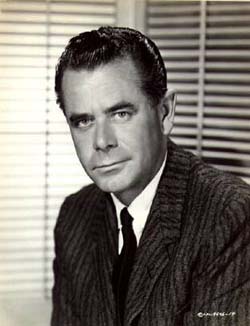

Glenn Ford

Glenn Ford

During the incarnation of SNL that numbered Phil Hartman, Dana Carvey and Dennis Miller amongst its cast, there was a sketch one season that was a send-up of a miniseries the previous television season positing a Soviet invasion of the US. In the SNL version, the Canadians had - for reasons that were never made clear - invaded the US, and everyone was saying "about" and "couch" in strange ways and uttering "eh?" at the end of nearly every sentence. This was, of course, satirical, but it does raise an interesting specter when one calls to mind all the highly-regarded actors and comedians who have come from north of the border. Glenn Ford, quintessential regular guy-in-the-wrong-place-at-the-wrong-time in Westerns, dramas and a host of other genres, Superman's Terran dad in recent Hollywood tellings of that tale, is one of these would-be invaders; he was born Gwyllyn Samuel Newton Ford in Sainte-Christine-d'Auvergne, Portneuf, Quebec.

The man who would become Supe's Daddy moved with his family to Santa Monica when he was eight years old; he became interested in acting in high school, doing extracurricular plays until he graduated, then joining the touring acting troupe West Coast. Unlike many a parent of future thespians, Ford's father was supportive of his acting career, but counseled his son to learn something else as well, so he'd have the proverbial job to fall back on. Taking his father's advice to heart to learn how to take apart a car and then put it back together, or build a house from the ground up, doing all the work yourself, he went the carpentry route, a skill he continued to utilize around his own home until frail health prevented him from continuing. As it turned out, though, he never needed that fall-back position; he was discovered by a talent scout and tested for Columbia Pictures in 1939, and the Columbia suits were sufficiently impressed to put him under contract. Ironically, however, Ford made his silver screen debut for 20th-Century Fox, with a bit part in the film Heaven with a Barbed-Wire Fence. He continued to kick around Hollywood doing small roles in a number of films, but like many actors of his generation, Ford took a break from moviemaking to fight in the Second World War. Enlisting in the Marine Corps Reserve, he saw active duty as a photographer and motion picture technician, making propaganda films to bolster the war effort back home and out American victories to the Axis powers. After the war ended, Ford returned to his movie career, although he remained in military service for several more decades. After enlisting in the Naval Reserve as a public affairs officer in 1958, he went on annual training tours to make radio, TV and personal appearances and film documentaries; and he saw service in Viet Nam scouting locations for a training film, where he traveled with a combat camera crew scouting locations for combat scenes for the film Global Marine. He eventually retired from the Naval Reserve in the 1970s, having attained the rank of captain.

His service to the US Armed Forces didn't keep him from being busy in Hollywood; on the contrary, Ford saw his career take off after the end of World War II. Bette Davis gave him his first high-profile role in the film A Stolen Life, but it was another film Ford made that same year that provided his breakout: The role of hapless Johnny Farrell, narrator and fall guy for Rita Hayworth's eponymous temptress in Gilda. This put Glenn Ford on the movie map, as it were, but while it ensured he was a busy actor, it would be another nine years before he scored another high-profile part, as the beleaguered inner-city teacher in Blackboard Jungle. That same year, 1955, began the high point of Ford's movie career; he starred in such A films as the Westerns 3:10 to Yuma, The Fastest Gun Alive and Cimarron; the dramas A Pocketful of Miracles - which reunited him with his benefactor Bette Davis - Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and Experiment in Terror; and the comedies Teahouse of the August Moon, Cry for Happy and Don't Go Near the Water.

As the '70s dawned Glenn Ford added television to his busy career, beginning with the excellent made-for-TV film The Brotherhood of the Bell. That 1970 tale of an all-powerful secret society that rewards its members and punishes anyone who crosses it or dares to try and expose the breadth of its influence was a landmark for the genre and was carried mostly on Ford's unassuming shoulders. A slew of TV roles followed, including leads in the odd Western/police procedural series Cade's County; the Hallmark Hall of Fame movie The Greatest Gift, which spawned Ford's only other stab at episodic television, The Family Holvak; the mini-series Once an Eagle and Beggerman, Thief; the dramas The Disappearance of Flight 412 and Where Have All the Children Gone?; and guest appearances on a number of series and talk and variety shows. And whilst Ford didn't abandon the silver screen entirely, his films were few and far between, and with the possible exception of the 1976 World War II extravaganza Midway, not of the quality of earlier in his career. In fact, Ford didn't appear in another high-profile film that also garnered critical and popular acclaim until he became Jonathan Kent, adoptive father to Christopher Reeve's Clark Kent, AKA The Man of Steel, in 1978's Superman.

As Fate would have it, that would also be Ford's last major film role. He appeared in a handful of projects the '80s and '90s, but most of those were on TV and none were major studio releases. Ford's later years were plagued by ill health and a number of trips to the hospital, as a series of strokes left him in increasingly fragile health, and save for a cameo appearance of sorts in the movie Superman Returns, he was not seen again on the big screen or small. When that great equalizer, the Angel of Death, enveloped Glenn Ford in its wings on August 30th, the world may have been deprived of Ford's presence, but not of the many wonderful acting performances enshrined in the everlasting celluloid world.

|

|

|

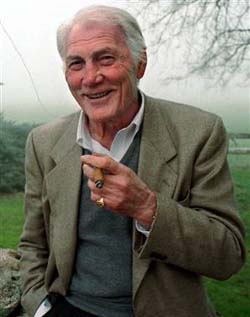

Jane Wyatt

Jane Wyatt

Jane Wyatt had many roles in a long and varied career, but it for playing two very different TV moms for which she is perhaps best known: the stay-at-home '50s iconic mother Margaret Anderson in Father Knows Best, and Amanda Grayson, the Terran mother of Vulcan/human hybrid Mr Spock on the original Star Trek series.

Jane Waddington Wyatt was born with a silver spoon in her mouth. The daughter of an investment banker on Wall Street and a drama critic for Catholic World magazine, Wyatt descends from a long line of WASPs and was listed in the New York Social Register. She attended the prestigious Chapin School and the equally tony Barnard College, but in her second year left to enter the apprentice school of the Berkshire Playhouse, playing a variety of roles during her six-month stint. After Berkshire Playhouse, it was on to Broadway, where she scored a chance to understudy Rose Hobart in Trade Wind, a move that cost her the Social Register listing (although she regained that distinction upon marrying an investment broker). Receiving favorable notices in a number of stage shows, she was eventually wooed away from the Great White Way to the silver screen, toiling under contract to Universal playing bit parts in a handful of films before scoring her breakout role - interestingly enough, for Columbia Pictures - as Ronald Coleman's love interest in Frank Capra's Lost Horizon. She worked steadily thereafter, appearing in such classics as None But the Lonely Heart, Gentlemen's Agreement and My Blue Heaven.

But her film career took an unexpected detour in the '50s. Like so many other Hollywood luminaries of the time, Wyatt saw her reputation unfairly tarnished by Tailgunner Joe's Communist witch-hunt The House Un-American Activities Committee. And even after Edward R Murrow showed McCarthy in all his small-minded, venal "glory", Hollywood proved reluctant to deal with anyone who had been blacklisted, or even tarred with the epithet "Communist sympathizer", no matter how ridiculous the charges and the man who brought them. Though she would appear in a few films in the decades that followed, her film career never completely recovered.

Wyatt sought refuge on the East Coast and the Broadway stage she knew and loved, appearing in a number of well-received plays and embracing the emerging medium of television with appearances on a number of Golden Age of TV Drama anthologies, including Lucky Strike Playhouse, Studio One and Your Show of Shows. It was during this time that Wyatt had her first shot at acting immortality, playing opposite Robert Young in the '50s family sit-com Father Knows Best. Wyatt won the Emmy for Best Actress in a Comedy three years running for her portrayal of Margaret Anderson, who was always immaculately turned out no matter what household chore she was performing, and who always had a sympathetic ear - and a glass of milk and cookies - for her brood. Ironically, she initially turned down the part that would make her a TV icon and role model; years later she explained that, having always played the lead, she didn't want to play "just a mother".

While one could argue that Margaret Anderson was "just a mother", Jane Wyatt's next maternal part was anything but. As Amanda Grayson, the human woman who married a Vulcan ambassador and gave birth to the eventual First Officer of the starship Enterprise, Wyatt brought along Margaret Anderson's warmth, but also a wit and the gravitas and iron will one would expect of a schoolteacher who was willing to leave everything she knew to travel to an alien world for the sake of love. The role made her an icon to a second generation of TV watchers, and returned her to the silver screen in a big way when she reprised it in the fourth film outing for the TOS crew, The Voyage Home.

But most of the remainder of Wyatt's acting career was on television, with guest appearances on a number of series and roles in a number of TV movies, including a Father Knows Best reunion movie (she also re-teamed with Robert Young in his next TV incarnation, Marcus Welby, MD, along with the future Mr Barbra Streisand, James Brolin). As the 20th century drew to a close, Wyatt took fewer acting roles, preferring to focus on her work for the March of Dimes, a charity for which she was a staunch supporter and ardent fundraiser throughout her life. Her last recurring role on episodic television was as Katherine Auschlander, wife of Dr Donald Auschlander on St Elsewhere. When she shuffled off her mortal coil on October 20th, she left behind her a body of work that any actor would be proud of, and two iconic roles as mothers that guarantee she will always be remembered.

|

|

|

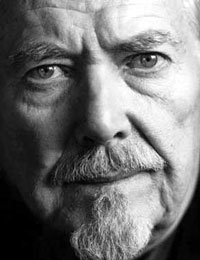

Jack Palance

Jack Palance

Jack Palance was the quintessential Hollywood villain, yet he is largely remembered oday for his performance at an awards show. Upon winning the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role in City Slickers - a rare comedy outing - instead of taking his award and giving the customary thank-you speech, he instead dropped to floor and did a number of one-handed push-ups, much to the amusement and amazement of his peers and the viewing audience. Whether that moment garnered him more work - as he later explained, he was attempting to show casting directors there was plenty of life in the old bird yet - it certainly made him a shoe-in for future Best of the Oscars film-clip reels.

But Jack Palance took a circuitous route to that Academy Awards stage, and to the art of acting itself. Born Volodymir Ivanovich Palahniuk in Pennsylvania coal country, Palance watched his father die a slow and much-too-early death from black lung disease. Although he followed his father into the only real job available for unskilled men in the area, Palance knew from early on that it wasn't the life for him, and fortunately, he had a ticket out: a consummate athlete, Palance received a football scholarship to the University of North Carolina, but only stayed a couple of years before turning his attention to professional boxing. Fighting under the name Jack Brazzo, Palance actually made quite a good go at being a pugilist, winning 12 of his 14 bouts. But prizefighting didn't really capture young Jack's interest either, and when World War II broke out, he followed the path of many a young man and enlisted in the Air Force, become a bomber pilot. After a horrific crash in which his airplane caught fire, his flying days also reached their end; ironically, the resulting scars from the burns and the resulting reconstructive surgery helped Palance when he finally turned to acting. Before reaching that point, though, Palance studied journalism at Stanford University, eventually taking a job as a sportswriter at the San Francisco Chronicle and doing radio. Then the acting bug bit, and Palance was launched into his next - and final - career choice.

Palance found success on the stage fairly quickly, going from his stage debut in The Big Two to understudying Marlon Brando for the Broadway version of A Streetcar Named Desire. He went on take the lead in plays such as The Vigil and The Silver Tassel. He received a great deal of recognition for his plum part in Darkness of Noon, and the resulting Theatre World Award for Promising New Personality brought him to the attention of Hollywood, where he went under contract with 20th-Century Fox. silver screen success came as quickly to Palance - initially billed as Walter Jack Palance - as it had on the stage; he scored big in his film debut as a fugitive carrying the bubonic plague in Panic in the Streets. After his second film, The Halls of Montezuma, allowed him to showcase his boxing talents, Palance got the notice of the Academy with his third film, Sudden Fear. In the first of his back-to-back Best Supporting Actor Oscar nods, Palance played the struggling actor husband who plots to kill his successful actress wife (Joan Crawford); he followed this up for what was arguably his iconic role - well, until the one-armed push-ups, anyway - as Alan Ladd's gunslinger nemesis in Shane.

His career as the archetypal movie villain took off from there, working steadily on both sides of the Atlantic and moving back-and-forth between the big and small screens. He was quite popular with the makers of spaghetti Westerns, seeing a lot of work in Italy; he also appeared on many of the anthology series from the so-called Golden Age of TV Drama, including Studio, Zane Grey Theatre and Playhouse 90. It was on this last anthology that Palance played a rare sympathetic role, that of aging boxer Harlan "Mountain" McClintock in Rod Serling's Requiem for a Heavyweight; the role garnered Palance his first piece of shiny metal for his mantelpiece, as he took home the Emmy for Best Single Performance by an Actor (yes, the names of the Emmy categories have changed over the years).

Palance stayed busy throughout his long acting life, playing mostly villains - both intentional and accidental - and taking on the occasional hosting gig - Ripley's Believe It or Not! showed off that signature bass rumble to perfection - until his later years, when he displayed an unexpected talent for comedy, which brought home that little bald man of gold that actors so cherish. Palance also brought out his more artistic side during his latter years, becoming both an exhibited painter and a published poet, in addition to raising a family and running his own cattle ranch.

Although Palance demonstrated quite effectively during the now-infamous acceptance speech that there was, indeed, life in the old bird yet, his acting roles were fewer as the 20th century drew to a close, and as the new millennium dawned, Palance took to the screen on fewer occasions, making his final appearances on television, the last being in the 2004 TV movie Back When We Were Grown-Ups. When that brief candle finally flickered and went out on November 10th, that sometimes-menacing/always thrilling bass rumbled no more, and that somewhat ominous smile relaxed into peaceful repose, the celluloid world lost one of its best villains and gentlest of men.

|

|

|

Robert Altman

Robert Altman

Robert Altman, he of the long tracking shots, the overlapping dialogue, and the tendency to let actors improvise to their hearts' content, started out as a writer.

Well, if you want to get technical about it, he started out as Robert Bernard Altman in Kansas City, Missouri, but after attending a military academy, he enlisted in the Air Force when World War II came along, serving as a co-pilot on B24 bombers. It was during his Air Force training in California that Altman became entranced with the klieg lights of Hollywood, and after his discharge, he went straight back to LA and embarked on a show business career.

After an unsuccessful go as an actor, he contributed to a screenplay for the United Artists film Christmas Eve, then sold RKO the script for a picture entitled Bodyguard, and he was on his way...or so he thought. After moving to New York and teaming with George W George, he co-wrote a number of published and unpublished screenplays, musicals, novels and magazine articles, and for all the success he had, he might even have tried a few greeting cards for all we know. Failing to make big money in New York, Altman returned to Hollywood, where his next idea was to tattoo ID numbers on cats and dogs so they could be returned to their owners if they ever became lost, a process he named Identi-Code. Although he managed to somehow tattoo President Harry Truman.s dog, his company soon went bankrupt, and he returned home to Kansas City, his tail tucked between his legs, to regroup and get going on his movie career again.

This time, Altman decided to move out from behind the typewriter and take up a spot behind the camera. It may surprise many people to learn that Kansas City actually had a big film production firm, the Calvin Company, and a friend recommended Altman to be hired. It was in the process of making some 65 industrial films that Altman learned to do quick set-ups and work within schedules and budgets, and also learned about the other tools needed to make a movie, from lighting to sound to set decorating. Once he felt he.d learned all he could at Calvin, Altman began taking leaves from the company to travel back to Hollywood, but for some reason, he still tried to make a career out of scriptwriting instead of directing. Consequently, each stay was short-lived, and each time, he returned to Kansas City and to Calvin. After the third such trip, Calvin made it quite clear that if he left again, he needn't return, so when he inevitably took another shot, his return to Kansas City didn.t take him back to his old firm. Instead, Altman was hired by a local producer to write and direct a teen exploitation flick called The Delinquents. Altman finished the script for what would turn out to be his first feature film in just one week, and shot it in two, using a cast of friends from local community theatres, family members and a few actors imported from Hollywood, and a crew mostly of people from Calvin who, like Altman, wanted to get the hell out of Dodge...er, Kansas City, and make it go of it in Tinseltown. Once the film was completed, Altman and his assistant director came out to Hollywood to edit the film, and never looked back. United Artists ultimately picked up the film for distribution, and it made a decent $1 million at the box office upon its release.

This was the ticket into Tinseltown that Altman had been waiting for, as the film caught the eye of the legendary director Alfred Hitchcock, who hired Altman to direct some episodes of his eponymous TV anthology series. Several other television series and TV movies, with the occasional feature film thrown in. But it wasn.t until Altman took on the task of directing a script that came his way in 1969 after more than 15 (!) other directors had taken a pass that he had his first big-screen success. M*A*S*H, the anti-Viet Nam War film screed in Korean War guise, garnered Altman serious critical attention, not to mention the first of his four Oscar noms, and one of the five the film received. And Altman was finally well and truly on his way up in Hollywood. Few people may know, however, that Altman was not the only member of his family to make a few bob from M*A*S*H; his 14-year-old son, Mike, wrote the lyrics for the theme, Suicide is Painless. Altman once half-jokingly told Johnny Carson on the Tonight Show that his son made more money from M*A*S*H than he did (more than $1 million for the theme versus $70,000 for directing).

The '70s were a halcyon decade for Altman, with such popular and critical successes as McCabe & Mrs Miller, A Wedding and Nashville, amongst others. But when the '80s dawned, Altman hit a speed bump in his rise up the Hollywood ladder with the critically reviled Popeye, which although it has been perceived as a humongous bomb actually made a goodly amount of money. The rest of the decade wasn't a lot better for Altman, with his film output being decidedly hit-or-miss. But with 1992's The Player, a vicious satire of the internecine workings at a fictitious movie studio that revealed more of Hollywood's underbelly to the moviegoing audience, Altman found himself back at the top of the critical heap, although his re-burnished career in the eyes of the critics and the public didn't last for many films, and by the time his next critical success and commercial success, Gosford Park, made it to the screen at the dawn of the new millennium, Altman had become something of a industry anomaly: well-respected by critics and, particularly, actors, but not considered a reliable moneymaker by studios. Worse still, the moviegoing public, rightly or wrongly, saw Altman primarily as a filmmaker who purposely created not-easily-comprehended films to show that he was an artiste, as though popcorn films were beneath him, a perception that had begun during the high point of his career in the '70s and had only gotten stronger over time. In fact, Altman founded Lions Gate (since renamed Lionsgate) Studios during that decade in an attempt to ensure more artistic freedom, because if the audience was displeased with your filmmaking style, it was a fair bet Hollywood would soon come to feel the same.

Gosford Park helped change that perception. It was as densely packed with sometimes-overlapping dialogue, plotlines and characters as any Altman film, but its story of illicit love and murder amongst the upstairs and downstairs denizens of a sprawling English estate was more easily accessible. Gosford Park was also seen by many as Altman's best chance at finally taking home one of those little gold statuettes, something that - like many great directors - had consistently eluded him over the years, despite four previous nominations. But it was not to be, and Altman finally received a Lifetime Achievement Oscar in 2006 to recognize his long career that, in the Academy's words, "repeatedly re-invented the art form and inspired filmmakers and audiences alike". Altman proclaimed himself pleased during his speech that he had been given the award for his body of work, rather than being recognized for only a few films. He also revealed that, unbeknownst to anyone outside his closest circle, he had had a heart transplant a decade before; he even joked that a "lifetime achievement" award might have come too soon, as he felt he probably had another 40 years or so of filmmaking left in him.

Sadly, however, that was not to be the case, as leukemia shuttered his lens for all time on November 20th. But Robert Altman's film legacy is a master class in how to create a unique voice and translate that vision across a body of films that would make any director proud.

|

|

|

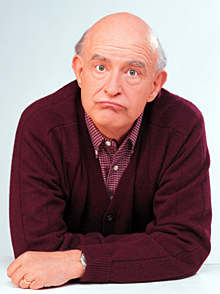

Peter Boyle

Peter Boyle

If you judged only from the characters he played, you'd think Peter Boyle was a very angry man. Even his comedy roles - Frankenstein's Monster and Frank Barone - were angry, albeit in a funny manner. But Peter Boyle entered the Christian Brothers monastery - they of the mid-range brandy - as a young man, eventually losing his calling when he was pulled towards the bright lights of the Broadway stage (not to mention the lovely chorines and wannabe actresses roaming around).

Peter Boyle is actually the second performer in his family with that name; his father was a well-known children's show host in Philadelphia. In his early days, however, Boyle showed little interest in acting; he pursued the usual amusements of young boys until his adolescence, when he began to consider a life of religious service. He wasn't long in the monastic life before he felt he hadn't truly been called to the vocation, but that it had instead provided him a way to make it through the vicissitudes of being a teenager, and once he was into young adulthood, he left the monastery.

Moving to New York, he studied acting under the legendary Uta Hagan, and worked as a bouncer, postal worker and waiter whilst building up his resume and awaiting his big break. After receiving good notices in the national company of The Odd Couple - and doing TV commercials on the sly - his break finally came when, as a member of the renowned Second City improv company, he replaced Peter Bonerz in the show Story Theatre, directed by Second City founder Paul Stills. His breakout film role came soon thereafter, when he starred as the bigoted taxi driver who commits a racial-based murder in Joe. Roles in The Candidate, Slither, and The Friends of Eddie Coyle soon followed, and Boyle became the sort of go-to guy for angry, menacing hulks.

It was during this period when his off-screen life became as interesting as his on-screen roles, if not more so. He joined Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland amongst the high-profile names protesting the Viet Nam war; he also met his future wife, Loraine Alterman, who was a photographer for Rolling Stone and a good friend of Yoko Ono. This led to Boyle's introduction to John Lennon, and they would remain close friends until Lennon's assassination in December 1980 (Lennon served as best man at Peter and Loraine's wedding). His activism showed in his film work as well; appalled at the enthusiastic audience reaction over the more violent outbursts of his screen breakthrough role, Boyle refused the lead in The French Connection, as well as other ultra-violent films. He also took a part in the anti-Establishment flick Steelyard Blues, another demonstration of his growing social conscience.

But it was a different sort of role that offered Boyle the chance to create an immortal screen character and participate in one of the most memorable sequences in any film. Cast as the creation of Gene Wilder's mad-ish scientist in Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein, Boyle displayed to film audiences the flair for comedy he honed at Second City; the pair's song-and-dance routine to Putting on the Ritz - a scene Wilder wrote that Brooks almost didn't film, afraid it wouldn't be very funny - indelibly imprinted itself upon the moviegoing public's mind. Interestingly, the Monster's monologue near the end of the film about his desire to inspire love mirrored somewhat Boyle's choices in his career path; having become prematurely bald at the age of 24, he was relegated to character parts instead of the leading-man roles he would have preferred pursuing.

Oddly enough, despite the brilliance of his comic performance in Young Frankenstein, Boyle was rarely cast in comedies, instead working steadily in both films and on television mostly assaying roles that exposed the seamy underside of the human character, appearing in such films as Taxi Driver; as Joseph McCarthy in Tail Gunner Joe; and as the homicidal Fatso in the TV remake of From Here to Eternity. It was in 1996 that Ray Romano tapped Boyle to play his TV dad on the hit sit-com Everybody Loves Raymond. Boyle's turn as the dyspeptic, curmudgeonly patriarch of the elder Barone clan won him acclaim and a new audience, although he - alone of all the cast members - never received an Emmy, despite being nominated seven times. Boyle did win an Emmy, though, for a guest-starring role on The X-Files, as well as a Screen Actors Guild award as part of the Everybody Loves Raymond ensemble.

Apart from playing Billy Bob Thornton's father in Monster's Ball - another bigot role - the roles Boyle took near the end of his acting days were all comedies, where he played variations on the curmudgeon-with-a-heart-of-gold that he portrayed on Everybody Loves Raymond. Though he returned to acting after a 1990 stroke and a 1999 heart attack, he finally met with the Ferryman on December 12th after a battle with bone-marrow cancer. No doubt St Peter is being regularly entertained by a live-and-in-person rendition of Putting on the Ritz on a regular basis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|